7Deliver Something

They'll Always Remember

Create a S.T.A.R. Moment

Create a moment where you dramatically drive the big idea home by intentionally placing Something They’ll Always Remember—a S.T.A.R. moment—in each presentation.

It should be so awe inspiring or so dramatic that the audience can’t help chatting about it later and reporters put it in their headlines. S.T.A.R. moments extend the conversation beyond your presentation and can help your message go viral.

If you’re speaking in front of a group that sees lots of presentations—like a customer who’s evaluating several vendors or a venture capitalist firm—success means standing out in their minds a couple of weeks after they’ve seen your presentation, when they’re ready to make a decision. Your goal is to make them remember YOU over all the other presenters they saw.

The S.T.A.R. moment should be a significant, sincere, and enlightening moment during the presentation that helps magnify your big idea—not distract from it.

There are five types of S.T.A.R. moments:

- Memorable Dramatization: Small dramatizations convey insights. They can be as simple as a prop or demo, or something more dramatic, like a reenactment or skit.

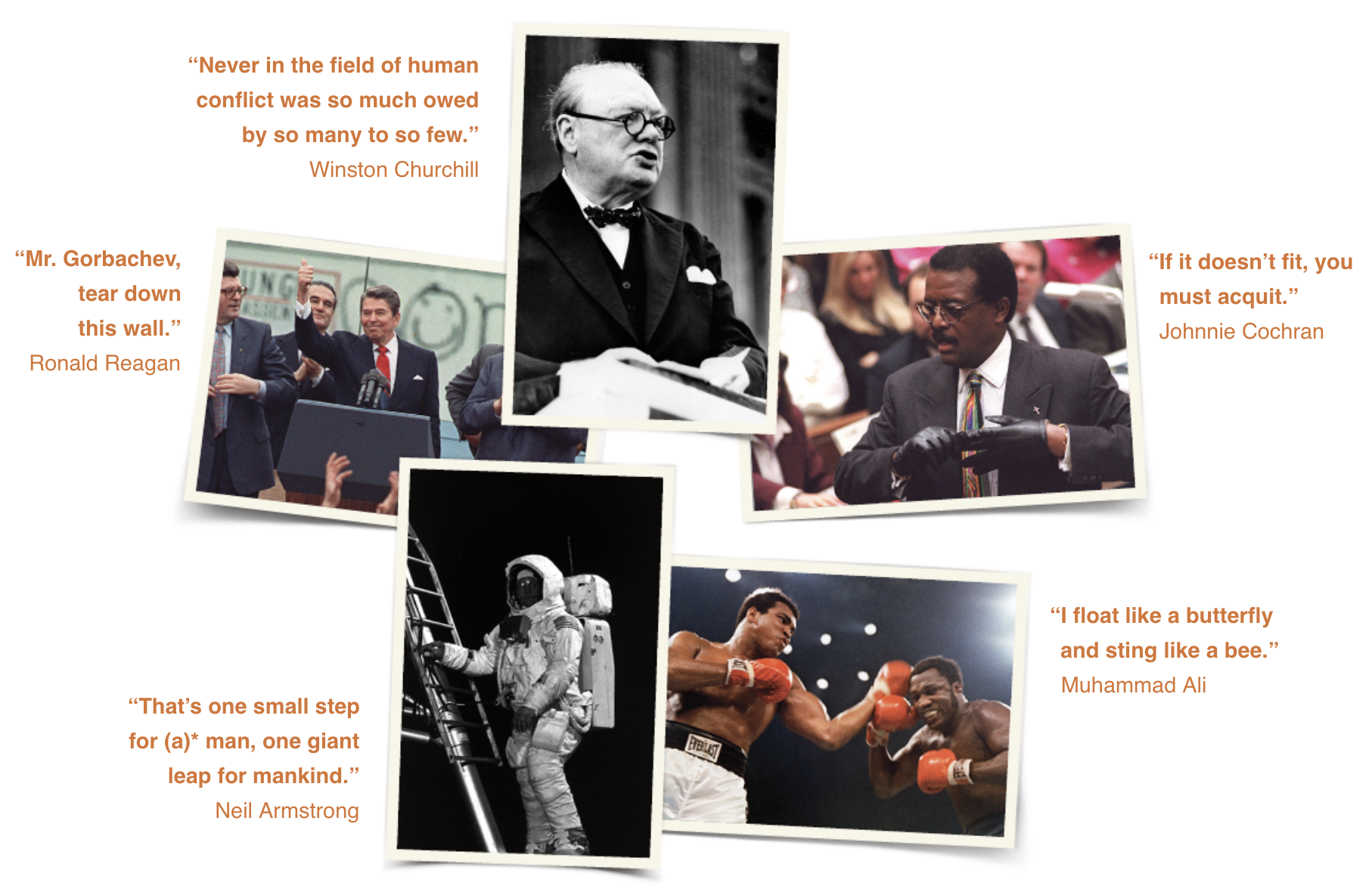

- Repeatable Sound Bites: Small, repeatable sound bites help feed the press with headlines, populate and energize social media channels with insights, and give employees a rallying cry.

- Evocative Visuals: A picture really is worth a thousand words—and a thousand emotions. A compelling image can become an unforgettable emotional link to your information.

- Emotive Storytelling: Stories package information in a way that people remember. Attaching a great story to the big idea makes it easily repeatable beyond the presentation.

- Shocking Statistics: If statistics are shocking, don’t gloss over them; draw attention to them.

The S.T.A.R. moment shouldn’t be kitschy or cliché. Make sure it’s worthwhile and appropriate, or it could end up coming off like a really bad summer camp skit. Know your audience and determine what will resonate best with them. Don’t create something that’s overly emotionally charged to an audience of biochemists.

S.T.A.R. moments create a hook in the audience’s minds and hearts. They tend to be visual in nature, and give the audience insights that supplement solely auditory information.

Famous S.T.A.R. Moments

RICHARD FEYNMAN

Richard Feynman was one of the investigators of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. Early on, he identified the likely cause of the explosion as a rubber O-ring that failed. To dramatize his conclusion, he took an identical O-ring, clamped it so it was curled and immersed in a cup of ice water. At just the right moment, he loosened the clamp and the rubber very slowly uncurled. “…[F]or more than a few seconds,” he said, “there is no resilience in this particular material when it is at a temperature of 32 degrees.”1 This made a deep impression on the reporters who were there because they knew it should have uncurled in a millisecond.

Famous S.T.A.R. Moments

BILL GATES

Bill Gates aspires to solve some of the world’s most grave problems through his philanthropic activities—including malaria. In a 2009 TED talk, he first established the seriousness of the malaria problem by telling the audience that millions have died from malaria, and that at any given time about 200 million people are afflicted by it. He then pointed out that more money is spent on the development of anti-baldness drugs for wealthy men than on conquering malaria for the poor. Then he produced a jar full of mosquitoes and opened it so they could escape into the room, saying, “There’s no reason only poor people should have the experience.”2

Famous S.T.A.R. Moments

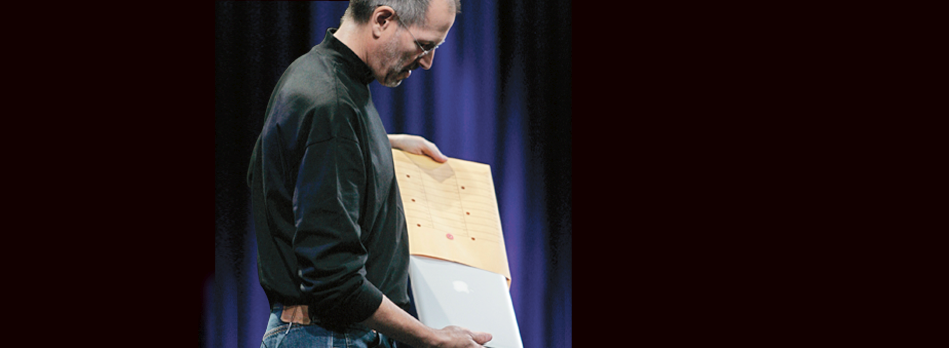

STEVE JOBS

Steve Jobs was a master at unveiling Apple products in intriguing ways. “This is the MacBook Air,” he said in January 2008, “so thin it even fits inside one of those envelopes you see floating around the office.” With that, Jobs walked to the side of the stage, picked up one such envelope, and pulled out a MacBook Air. The audience went wild as the sound of hundreds of cameras clicking and flashing filled the auditorium. “You can get a feel for how thin it is. It has a full-size keyboard and full-size display. Isn’t it amazing? It’s the world’s thinnest notebook,” said Jobs.3

Case Study: Michael Pollan

Memorable Dramatization

If ever there was a natural storyteller, it’s Michael Pollan. His books, including The Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Defense of Food, teach people the sources of their food. They have completely changed the way Americans look at the existing food system.

When he was asked to speak at Pop!Tech, he wanted to make a lasting impression on the audience about one particular point. He and his team had calculated the amount of crude oil it took to make one double cheeseburger at a fast food outlet. The quantity was shocking, and he wanted to make sure the audience remembered it.

At the start of the presentation when he walked on stage, Pollan carried a paper bag from a fast food chain with him. He explained that it was, “a little something for later” and put it down on a table in the middle of the stage. Then he began his presentation, leaving his listeners in a state of suspense about the bag.

Later on, when he started talking about the connections between crude oil and our food supply, he said, “I want to show you how much oil goes into producing this [cheeseburger].” First, he took a cheeseburger out of the paper bag. Then he pulled out a container full of oil and an eight ounce glass. He poured the oil into the glass until it was full. “But that’s not all,” he said. “You need another eight ounces.” He reached down under the table and picked up a second glass and filled it. Then he filled a third, and part of a forth. It was an incredibly graphic demonstration of just how much oil (26 ounces) it takes to produce one double cheeseburger.

Repeatable Sound Bites

You know you did a good job communicating your message when it’s easy for people to recall it, repeat it, and communicate it to others. The way to do this is to implant a handful of succinct, clear, and repeatable sound bites in your presentation—ones that your audience will remember without effort after they’re gone.

A carefully crafted sound bite can work as a S.T.A.R. moment—not only for those who attend your presentation, but also for those who encounter it second hand through conventional broadcast channels or social media.

- Press: Coordinate key phrases in your talk with the same language in the press release. Repeating critical messages verbatim ensures that the press will pick up the right sound bites. The same is true for any camera crews that might be filming your presentation. Make sure you have at least a fifteen- to thirty-second message that is so salient it will be obvious to the reporter that it should be featured in the broadcast.

- Social Media: Create crisp messages. Picture each person in the audience as a little radio tower empowered to repeat your key concepts over and over. Some of the most innocent-looking audience members have fifty thousand followers in their social networks. When one sound bite is sent to their followers, it can get re-sent hundreds of thousands of times.

- Rally Cry: Craft a small, repeatable phrase that can become the slogan and rallying cry of the masses trying to promote your idea. President Obama’s campaign slogan, “Yes We Can,” originated from a speech during the primary elections.

Take time to carefully craft a few messages with catchy words. When Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, he had to wait six hours and forty minutes before emerging from the lander to take his first step on the moon. He used that time to craft his statement. Phrases that have historical significance or become headlines don’t just magically appear in the moment; they are mindfully planned.

Once you’ve crafted the message, there are three ways to ensure the audience remembers it: First, repeating the phrase more than once. Second, punctuating it with a pause, that gives the audience time to write down exactly what you said. And third, projecting the words on a slide so that the message is received visually, as well as orally.

BELOW ARE A FEW RHETORICAL DEVICES THAT CREATE A MEMORABLE SOUND BITE.

- Imitate a famous phrase: Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Imitation: Never give a presentation you wouldn’t want to sit through yourself.

- Repeat words at the beginning of a series: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…”

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities - Repeat words in the middle of a series: “We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed…”

Apostle Paul to the Corinthians - Repeat words at the end of a series: “…and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address

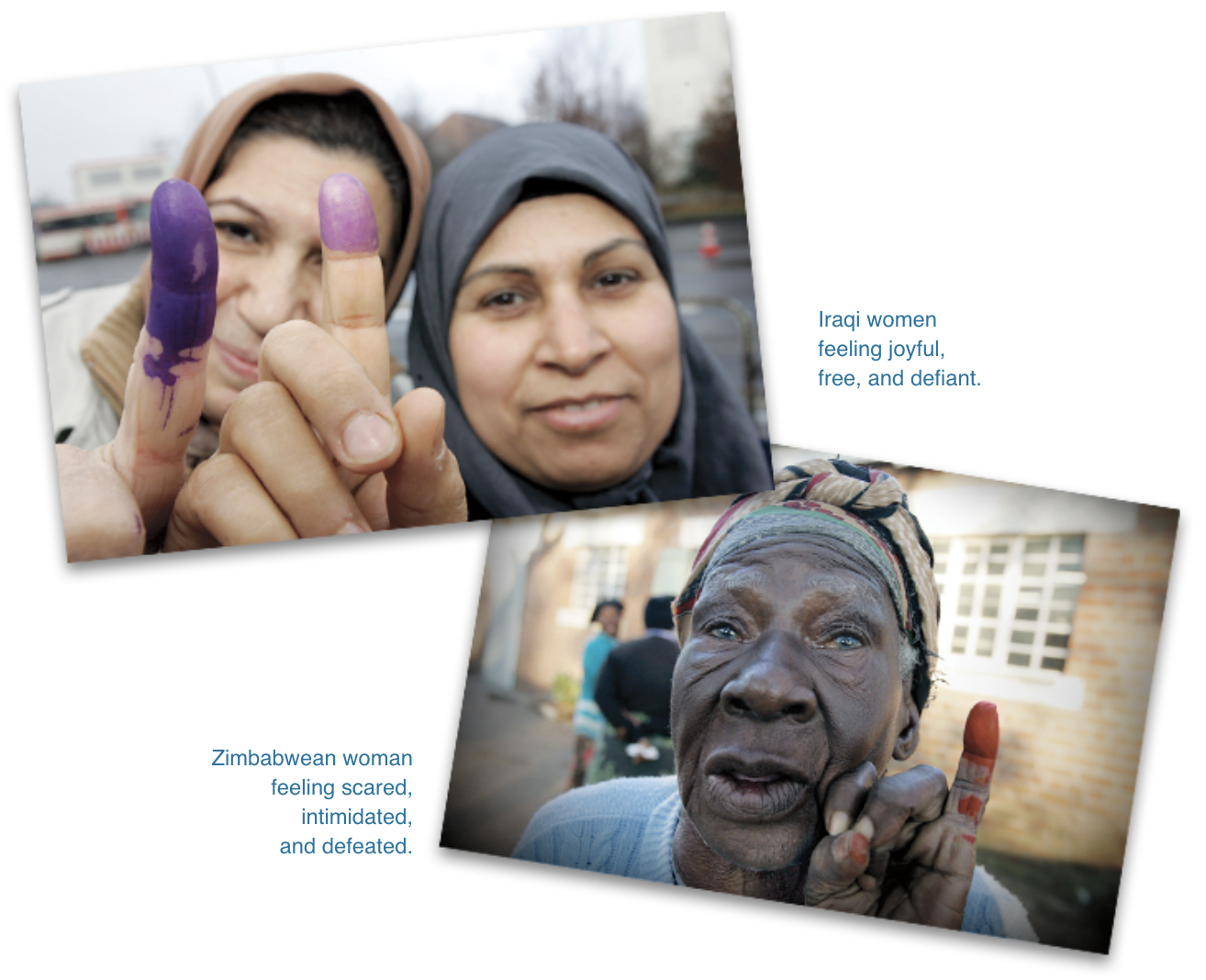

Evocative Visuals

Images have the power to evoke the full range of human emotion, from pleasure to pain. Eloquent verbal descriptions can create a strong impression, but frequently, a photograph or illustration will make a more vivid imprint in the hearts and minds of the audience. When the human mind recalls an image, it also recalls the emotion associated with the image.

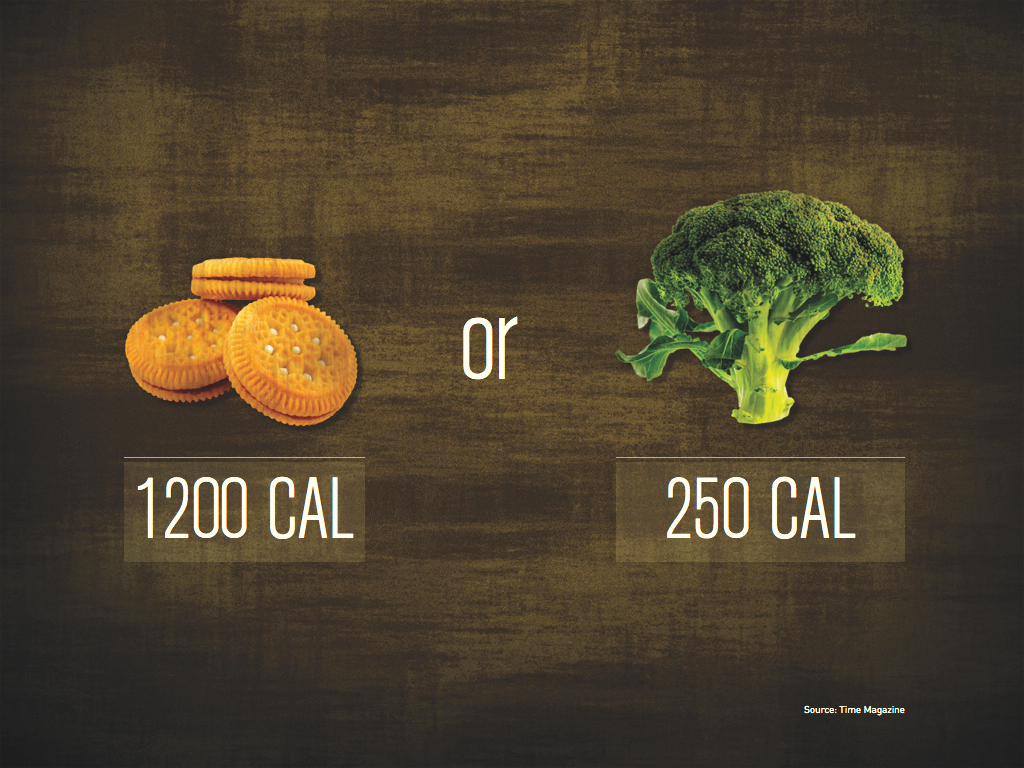

You can include slides in your presentation with one large full-screen image to emphasize a point, or place two images side by side as seen on the right to evoke conflicted emotions.

Two recent occasions were publicized on an international scale through images of ink-stained fingers. In one, fingers were stained to prevent double voting. In the other, fingers were stained to tyrannically enforce voting. Each evoked very different emotions.

January 30, 2005: Iraqis voted for the first time since the fall of Saddam Hussein. Militants tried to stop the voting by setting off dozens of explosives that shook Baghdad. Proud citizens raised their purple digits (showing they had voted) as gestures of support for democracy and in defiance of terrorist threats.

June 27, 2008: After Robert Mugabe was defeated in Zimbabwe’s presidential elections, he mandated a run-off ballot where he was the only candidate, and resolved to hold onto power through fraud, corruption, and intimidation. Voters in Zimbabwe were required to show their ink-stained finger to prove they had voted. If they didn’t, they could be beaten, forced to vote, and would face severe consequences at the hands of government agents. Using images often conveys emotional force that words cannot match—particularly when abstract issues like democracy and tyranny are involved.

Contrast Shows Ocean’s Importance

Conservation International uses dreamlike images of the ocean juxtaposed to rubbish washed up on the beach. The contrast is jarring and compels the audience to understand why the oceans are so important, be ready to take action to improve policy, change business practices, and make better choices in their daily lives.

Case Study: Pastor John Ortberg

Emotive Storytelling

Storytelling creates the emotional glue that connects an audience to your idea. Creating unique, inspirational messages every week is demanding, and Pastor John Ortberg of Menlo Park Presbyterian relies heavily on his own life stories to illustrate his messages.

Ortberg’s skill at using stories to communicate his messages is a hallmark of his unique style and appeal.

He takes whatever amount of time he needs to word-craft and story-craft his messages into a tapestry. He begins with a master theme from scripture, and then interlaces it with personal stories. It’s likened to the woof and warp of a loom. The latitudinal warp consists of the master theme and scriptural support, while the horizontal woof is the stories, which are like the yarn that shuttles back and forth to produce the patterns of the fabric.

The sermon analyzed on the next page was the first I heard Ortberg deliver. I was intrigued by its structure and its ability to move me. The master theme was “people can bring the Kingdom of Heaven to this Earth by showing love.” He sprinkled several stories through the sermon, but there was one master story that was referenced and carefully woven throughout: that of his sister’s rag doll, Pandy.

After telling the rag doll story at the beginning, he continued to use it like glue with references to raggedness throughout the sermon.

The master story conveyed that people want to be loved in spite of their ragged condition.

Ortberg’s Sparkline

The most interesting discovery about this analysis was how many times he amplified the gap between how broken and unloved we are on this earth (raggedness) and how love should be expressed (the kingdom). Those tick marks, along with how many times the audience laughed, run along the bottom of the sparkline.

Ortberg limits his sermons to 20 minutes or so. Each sermon has an overarching theme, stories and contrast between what is and what could be.

Case Study: Raunch Foundation

Shocking Statistics

In 2002, a small group of Long Island’s civic, academic, labor and business leaders gathered to discuss challenges facing the region and its potential for new directions. As a result of those meetings, The Rauch Foundation funded the Long Island Index to gather and publish data on the Long Island region. Their operating principle was, “Good information presented in a neutral manner can move policy.” The goal was to be a catalyst for action by engaging the community in thinking about its future from a regional perspective.

Even though the Long Island Index has served up good data about the past and present, the hope to drive action to make the future better hadn’t seen much traction.

The local Long Island newspaper, NewsDay, reported that “Last year, Index founder Nancy Rauch Douzinas challenged people to adopt a let’s-do-something-about-this attitude. But the attitude, like action, hasn’t materialized. So the Index is adopting an attitude of its own. It still will present data neutrally, and it won’t take sides, but it will be much more active in trying to make sure that its ideas and its sense of urgency don’t end when the lights come on after the annual presentation.”5

“For seven years, the Long Island Index produced many reports filled with facts and figures that told people how poorly our region was faring. When we shifted to telling the story visually, the reaction was electric. The information was the same, but the new format communicated the issues with an emotional urgency. The visual story moved citizens and elected officials to address the problems with an understanding that there was no more time to lose.” Nancy Douzinas, President, Rauch Foundation

So, at the 2010 press launch of the Index, The Rauch Foundation pulled out key statistics and incorporated that information into a presentation. Dramatizing the key statistics with images helped convey the inventiveness and sense of urgency that would be required to manage growth with better environmental outcomes. Titled The Clock is Ticking, this four-and-a-half minute presentation showed one image after another to drive home the idea that Long Island is in steady decline and must do something, right now!

Case Study: Steve Jobs

MacWorld 2007 iPhone Launch

Steve Jobs had the uncanny ability to make audience engagement appear simple and natural. His presentations compelled an audience’s undivided attention for an hour and a half or more—something that very few presenters can do.

“Steve Jobs does not deliver a presentation. He offers an experience.” Carmine Gallo6

Jobs was the quintessential presenter; he handled the content, contrast and delivery all very well. His reputation for marketing brilliance had the audience coming in to the presentation in a frenzied state of excitement, and he brilliantly kept them there with dramatic suspense and an intriguing delivery. This is an uncommon skill for a CEO, or anyone, for that matter.

Jobs purposefully built anticipation into each of his presentations—which have been described as an “incredibly complex and sophisticated blend of sales

pitch, product demonstration, and corporate cheerleading, with a dash of religious revival thrown in for good measure.”7 Over the years, he used every type of S.T.A.R. moment. Below are four from his 2007 iPhone launch presentation.

- Repeatable Sound Bites: During the keynote address, Jobs used the phrase “reinvent the phone” five times, the same phrase that Apple used in their press release. After walking through the phone’s features, he hammered it home once again: “I think when you have a chance to get your hands on it, you’ll agree; we have reinvented the phone.” The next day, PC World ran a headline stating that Apple would “reinvent the phone.”8

- Shocking Statistics: Instead of merely throwing out a large number, Jobs provided context so the audience could relate to the true scale of the number. “We are selling over five million songs a day now. Isn’t that unbelievable? Five million songs a day! That’s 58 songs every second of every minute of every hour of every day.”

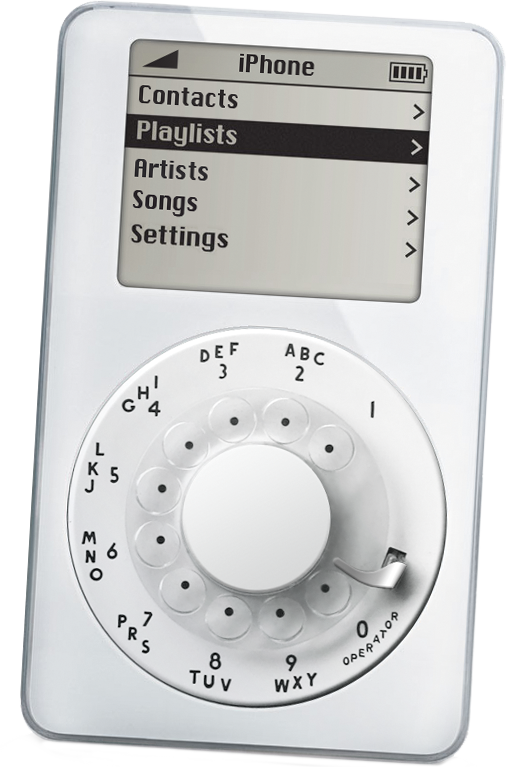

- Evocative Visuals: The audience laughed when he said, “Today Apple is going to reinvent the phone, and here it is…” He then showed the iPod you see here to look like it had an old rotary dial on it to tease the audience.

- Memorable Dramatization: In earlier presentations, Jobs had pulled an iPod out of his coin pocket and removed a MacBook Air from an inter-office envelope. For this launch, a feature of the product itself created the dramatic moment. The new interface was so revolutionary the audience gasped the first time he used the scrolling feature.

Later, Jobs said, “I was giving a demo to somebody a little while ago at Apple. I finished the demo and I said, ‘What do you think?’ He told me this: ‘You had me at scrolling.”

On his sparkline you will see three levels of vertical tick marks underneath the sparkline. The first two levels are where the audience laughed and clapped. Laughing and clapping are physical reactions to what he said. This is story at its finest, his audience physically reacts to him in almost 30 second increments. The third level of tick marks represents every time Jobs marveled at his own product. Even though he was very familiar with the iPhone he marveled at it affectionately as if he’s seeing it for the first time. Approach your presentations and products with that much passion and you too may change the world.

CEO, Apple Inc.

Jobs' Sparkline

Steve Jobs could hold an audience’s attention for a full 90 minutes. How did he do that? Looking at the iPhone launch presentation, the audience laughed 73 times and clapped 105 times and Jobs marveled at his own product 137 times in 90 minutes.

If Ronald Reagan is The Great Communicator and Richard Feynman is The Great Explainer, might Mr. Jobs be The Great Presenter?

Chapter 7 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.

In Summary

It’s a great feeling to deliver a presentation after which everyone is buzzing with excitement at the water cooler; or your presentation is splashed on front-page news; or social media sites pick it up—and suddenly millions have seen your presentation.

The presentations that get repeated have memorable moments in them. These moments don’t happen on their own; they are rehearsed and planned to have just the right amount of analytical and emotional appeal to engage both the minds and hearts of an audience.

Captivate your audience by planning a moment in your presentation that gives them something they’ll always remember.

Rule #7

Memorable moments are repeated and retransmitted so they cover longer distances.