8There's Always Room

to Improve

Amplify the Signal, Minimize the Noise

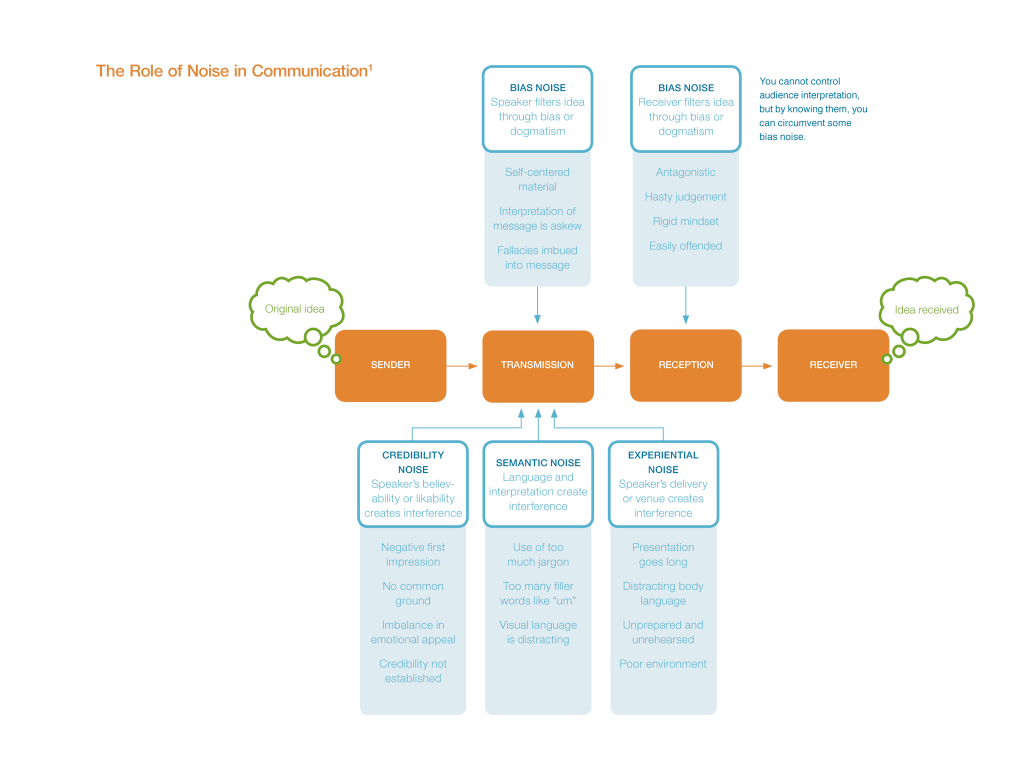

A presentation broadcasts information to an audience in much the same way that a radio broadcasts programming to listeners. Thus, the signal’s strength and clarity determines how well information is conveyed to its intended recipients. Communication is a complex process that has many points at which the signal can break down. Once a message has left its sender, it is susceptible to interference and noise, which can cloud its intention and compromise the recipient’s ability to discern the meaning.

Communication has the following parts: sender, transmission, reception, receiver, and noise. The message can become distorted at any step of this process. Your top priority is to ensure that the message-carrying signal is free from as much noise or interference as possible.

In 1984, I began my own high-tech career selling custom, high-frequency cable assemblies. Each cable was custom engineered to meet an extensive list of specifications. Each engineer and plant employee was tasked at ensuring that every step in the making of the product lowered the noise margin and protected the signal’s quality. Our company used progressive materials to insulate wire, performed raw material testing, and fashioned gold-plated terminators. Extreme detail was implemented at each stage of product development and each product was tested before being shipped. We didn’t ship products that fell short of a tight impedance tolerance, because they wouldn’t work for the client’s application. One tiny fault would render the cable ineffective.

This holds true for crafting a world changing presentation. The signal-to-noise ratio is an important factor in how well your message is received, and it’s your job to minimize the noise. If the audience receives

a message that includes any interference, they receive distorted information. You must expend energy minimizing the noise in each step of the communication process to ensure that a crystal clear message gets through to your audience.

There are four main types of noise that can interfere with your signal: credibility, semantic, experiential, and bias noise. The graphic on the previous page shows where the various types of noise occur in communication. Your job is to minimize the noise as much as possible at each step of the process.

This section will address some of the factors that create noise. Noise can be reduced or eliminated through careful planning and rehearsing.

Give a Positive First Impression

The old adage is true: You never get a second chance to make a first impression. But is telling a joke or using a cheesy icebreaker really the way to start?

Think through how you want the very beginning of your presentation to affect your audience. What’s the first thing you want them to experience? What kind of first impression do you want to make on them? What’s the mood you want your introduction to create? Remember, what you say isn’t the only thing that creates an impression. The room where you’re presenting, the lighting, the music (if you choose to play music), the items the audience may find on their chairs, pre-presentation images on the screen, how you’re dressed, how you enter the room—all of these things work together to create the first impression.

Even though you very much want the audience to like you for your mind and not your appearance, their first impression is going to be based on how you look—at least for a while. The people in the audience will mentally categorize you in just a few seconds, and then decide whether or not you’re a person they can connect with.

Aristotle argued against letting first impressions influence the perceived validity of the content. He said, “Trust… should be created by the speech itself, and not left to depend upon an antecedent impression that the speaker is this or that kind of man.” In ancient Greece, however, oration was very sophisticated, and followed many rules. Most people in today’s audiences are a bit shallower, and will use the first few crucial seconds to judge your credibility.

Many people fear public speaking because they’re afraid of being judged. You need to realize that you have the power to shape and control the first impression that people use as a basis for judging you.

Don’t let yourself be intimidated. The things on people’s minds while they’re waiting for a presentation to begin would amaze you. The following chat streams let you see—and take comfort in—just how shallow and mindless they are. These are the real comments of audience members just before an actual presentation started:

“Scalding hot coffee in a room packed with socially inept people means I now have a burned hand.”

“I hope there’s no line in the ladies room.”

“I hope she has gone to Toastmasters since the last time she spoke.”

“Aw man, I missed mimosas at registration this morning.”

“Dead crowd here.”

“If anyone wants to meet me, I’m sitting in the back.”

Yep, that’s the stuff on their minds before you present. Nothing earth-shattering. Their expectations are pretty low and self-focused, so creating a memorable first impression with these folks shouldn’t be too tough.

First impressions do not have to be overly dramatic or gimmicky. They’re about revealing your character, motivations, abilities, and vulnerabilities. You’re asking the audience to walk in your shoes, and they don’t even know if they like you yet, let alone your taste in shoes. So establishing who you are and your own likeability is paramount.

Also, don’t forget that part of the audience’s first impression is formed before you even enter the room, so pay attention to communications that you sent before the presentation. This includes the style of the invitation, the framing of the agenda, the wording of e-mail reminders, and of course, your bio. All of these pre-presentation interactions count in creating the audience’s real first impression, so it’s important to make sure they’re appropriate and serve your objective.

Successful first impressions help the audience identify with you and your message. When you introduce yourself, all audiences will be looking for similarities and differences. It’s their nature! So, as they’re sizing you up, make these similarities and differences as clear as possible so you can get beyond this phase quickly. Focus on creating a sense of common identity between you and the people you’re trying to influence.

The audience learns a lot about you based solely on how you appear for the first time.

When I first started hosting Slide:ology workshops here at Duarte, I kept trying to squeeze an entire workday in before the workshop started at 9:00 AM. I’d blast into the room, test the projector, cross check files, and jump into the material. I was busy, distracted, and wound up

pretty tight. Any of the poor early birds got a clear “I’m super busy and was trying to squeeze in an entire workday before you got here” message. I noticed that the crowd wasn’t warm or receptive to me.

Then, I attended a workshop hosted by a friend of mine, and author of Presentation Zen, Garr Reynolds. Before his presentation, he entered the room upbeat and engaged, shook hands, asked attendees questions, and set a completely different tone. They perceived that he had all the time in the world for them. Right off the bat, he came across carefree and warm. Even though our content was of similar nature, he had them eating out of his hands before he said the first word, and I didn’t.

Hop Down From Your Tower

Have you ever sat through a presentation where—even though the presenter sounded super smart—you had no idea what she really said?

Most highly specialized fields like those in science and engineering have a distinct lexicon that’s used every day—one that’s familiar to experts, but foreign to anyone not in that field. Innovation is happening very quickly, and each new field generates a plethora of new terms weekly. If you’re an expert, you can’t assume that people have kept up with your field. Using highly specialized jargon when you’re addressing non-specialists can hamper your efforts and reduce the amount of help you receive from them—solely because they don’t understand what you’re saying. You need to modify your language so it resonates with the potential collaborators and funders of your idea.

Before specialists acquired their new-fangled vocabulary, they used the common language of the masses. But as they studied their narrow fields, specialized terms and jargon snuck in. It’s like the folks who built the Tower of Babel. Originally, they all spoke a unified language. But due to their pride, their language was confused and they were scattered throughout the earth.

When presenting to a broad audience, you need to go back to a common and unified language so your audience doesn’t scatter in confusion. Even though it’s fun to sound smart—and yes, to confound others with your awesome smarty-pantness—this hinders the adoption of your idea when you’re speaking to a group that isn’t as specialized as you are.

“Speaking in jargon carries penalties in a society that values speech free from esoteric, incomprehensible bullshit. Speaking over people’s heads may cost you a job or prevent you from advancing as far as your capabilities might take you otherwise.” Carmine Gallo2

If your idea requires the use of special terminology, you must be prepared to translate it into intelligible words that laymen can understand. It’s imperative that you know how and when to switch between specialized and common language. Don’t choose words that fall outside your listener’s vocabulary.3 Tailor your language to what the audience uses.

For example, a great Nobel Laureate in Physiology, Barbara McClintock, discovered in the 1940s that genes are responsible for turning physical characteristics on or off. However, her groundbreaking research was greeted with skepticism and wasn’t fully understood until the 1970s because of her communication style. McClintock had a vivid inner vision and a rapid-fire delivery. She would often leap back and forth from microscopic observation, to model, to conclusion, to result—all in a single sentence! Most audiences were ill-prepared, or simply too lazy, to work hard enough to master the data that poured forth from her. The way she communicated caused her findings to lie hidden for years!4

Jargon isn’t confined to specialized professions. Many good ideas die because they fail to navigate the very organization where they originate. Different departments within the same entity often use different languages, which can create internal confusion. In some meetings, more acronyms are spoken than real words.

Niche language with which you may be comfortable can sound unintelligible to a broad audience. An audience will not adopt your idea unless they understand it.

Your idea’s perceived value will be judged not so much on the idea itself, but on how well you can communicate it.

Value Brevity

Presentations fail because of too much information, not too little. Don’t parade in front of the audience spewing every factoid you know on your topic. Only share the right information for that exact moment with that specific audience.

“Whether your audience includes the most powerful or the most humble, each considers his time worthwhile, for it is an irretrievable slice of his life.” Henry M. Boettinger5

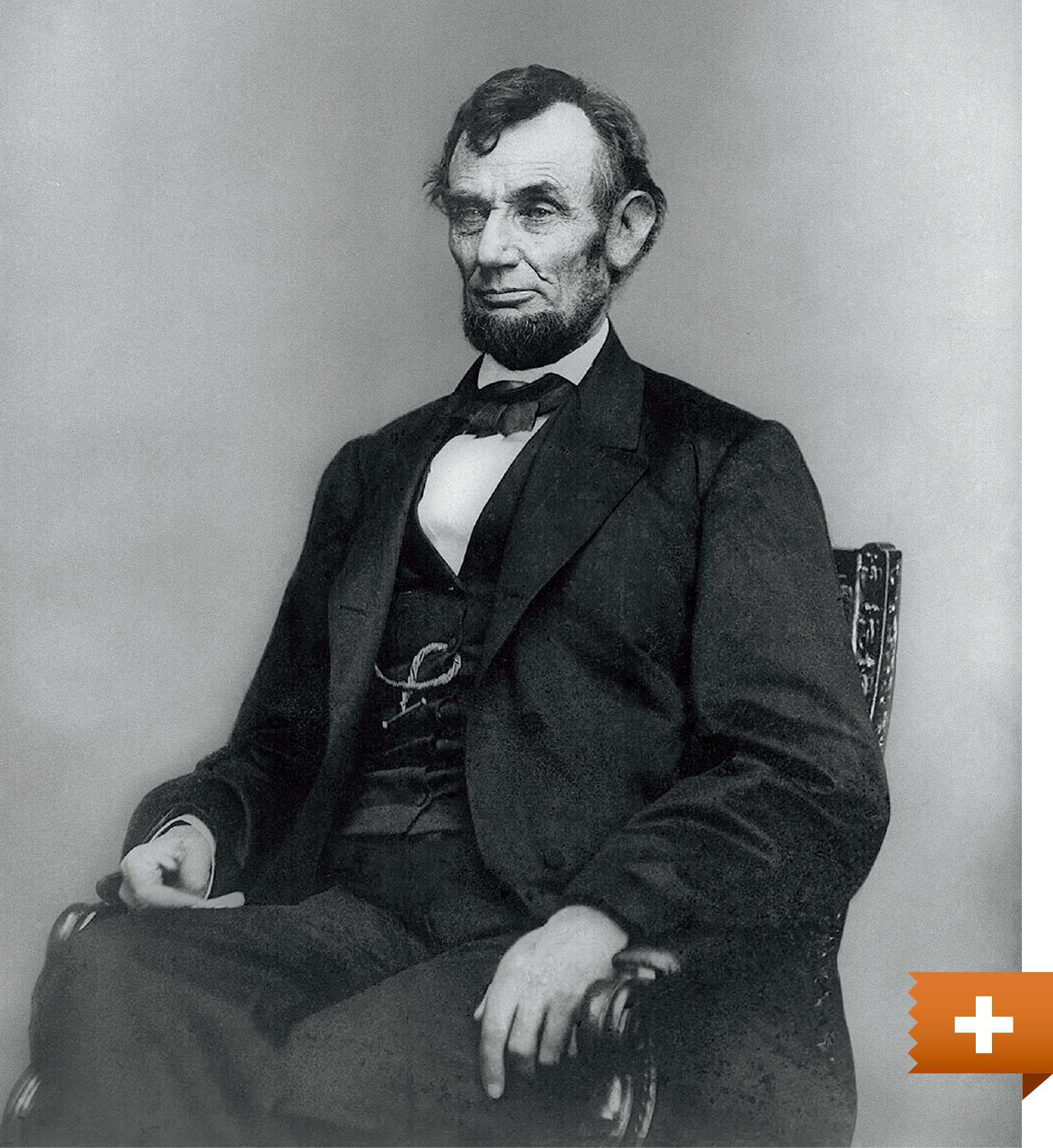

Abraham Lincoln constructed the Gettysburg Address with 278 words, and delivered it in just over two minutes. Though one of the shortest speeches in history, it is also considered to be one of the greatest.

The speech’s purpose was to dedicate the Gettysburg National Cemetery and eulogize the fallen. Though eulogists at that time traditionally took hours, Lincoln was so quick that the photographers were still setting up their equipment as he finished; hence we have no photos of him delivering the speech.

Most people aren’t even aware that Lincoln wasn’t the featured speaker that day. Edward Everett shared the platform and delivered a eulogy in the traditional style, spending two hours praising the virtues of the soldiers. The day after the speech, Lincoln received a note from Everett that complimented him for the “eloquent simplicity and appropriateness” of his remarks. Everett said, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”6

Lincoln was allotted two hours but only spoke for two minutes. Being so brief compelled him to be very clear about his central ideas. But in spite of its brevity, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address still follows all the key elements of the presentation form. He covers what is with a review of America’s historical values, the current state of the war, and the reason for the gathering. He shocks his listeners by telling them that they cannot dedicate or consecrate the ground, even though that’s what their purpose was in coming there.

Instead, he puts forth a call to action: that the audience resolve that the dead shall not have died in vain. He then describes the new bliss of a free nation.

One thing that will help you remain brief is to put your own constraint on the amount of time you present. Imposing a shorter timeframe requires you to be succinct. If they give you an hour, target a talk at forty minutes. Restriction of time forces clear structure and a filtering down process that leaves only imperative messages.

“If I am to speak for ten minutes, I need a week for preparation; if fifteen minutes, three days; if half an hour, two days; if an hour, I am ready now.” Woodrow Wilson

Wean Yourself from the Slides

Any slides you use during your presentation should serve as a stage-setting or backdrop; they should rarely be the sole focus for the message. You deliver the message, not the slides. People can only process one inbound message at a time. They will either listen to you or read your slides; they cannot do both.7

When you open a slide application to create a new slide, the default format you’re offered is appropriate for a report. If you fill the default master template with words, it will take your audience twenty-five seconds to read the slide. Since they can’t read and listen at the same time, if you have forty slides multiplied by twenty-five seconds, they’ll be reading for over sixteen minutes of your presentation, instead of listening to you.

By planning the structure first, you can ensure the presentation won’t go too long. Audiences squirm when a frustrated presenter delivers for fifty-five minutes and then says, “Oh man, where’d the time go, I still have forty-three slides, so hang on, I’ll get through them in the next five minutes.”

If you plan a solid structure with the timeframe in mind, it guarantees you will stay within the time constraints.

What’s the right number of slides? There is no definitive “right number” of slides for a presentation. It’s all driven by the personal delivery and pacing of the presenter. So the answer is “as many as necessary to get your point across.” Hollywood scene and story analysts adhere to the practice of making scenes no longer than three minutes for fear of losing the audience’s interest.8 Three minutes! Odds are high that your audience is losing interest every three minutes too, and to compound the problem, you don’t have a $100 million blockbuster movie budget. Because the presentation medium is more static than cinema, don’t stay on a slide for any more than two minutes. Changing the visuals as often as possible helps regain audience attention.

Most presentations have multiple points per slide and are a document, not a slide. If you choose to put only one idea per slide, you’ll have more slides than are traditionally seen in a slide deck that makes multiple points-per-slide.

I was invited to speak for forty-five minutes at a luncheon keynote. The organizers asked for the slides to be submitted thirty days in advance, so I crafted the message, rehearsed it, and sent a deck with 128 slides.

A week before my talk I got a call from the organizers telling me that the keynote was reduced to twenty minutes and to resubmit slides. So I trimmed, rehearsed and timed it for twenty minutes. The day of the presentation, the emcee reminded me to “stay within the forty-five minute slot because people enjoy a Q&A.” Shocked, I told him that they’d reduced the speaking slot to twenty minutes. “No, you have an hour. We just told you twenty minutes because you had too many slides and we thought you’d go long.” Internally I was shouting, “I CREATE PRESENTATIONS FOR A LIVING” but on the outside I smiled and said “Well, there’ll be a forty-minute Q&A, I hope they have a lot of questions.”

Slide Content Reduction

Only put elements on your slides that help the audience recall your message. There is a range of slide content density. The number of words and amount of time it takes the audience to process the information determines whether you’ve created a dense document or a true visual aide to project onto the screen.

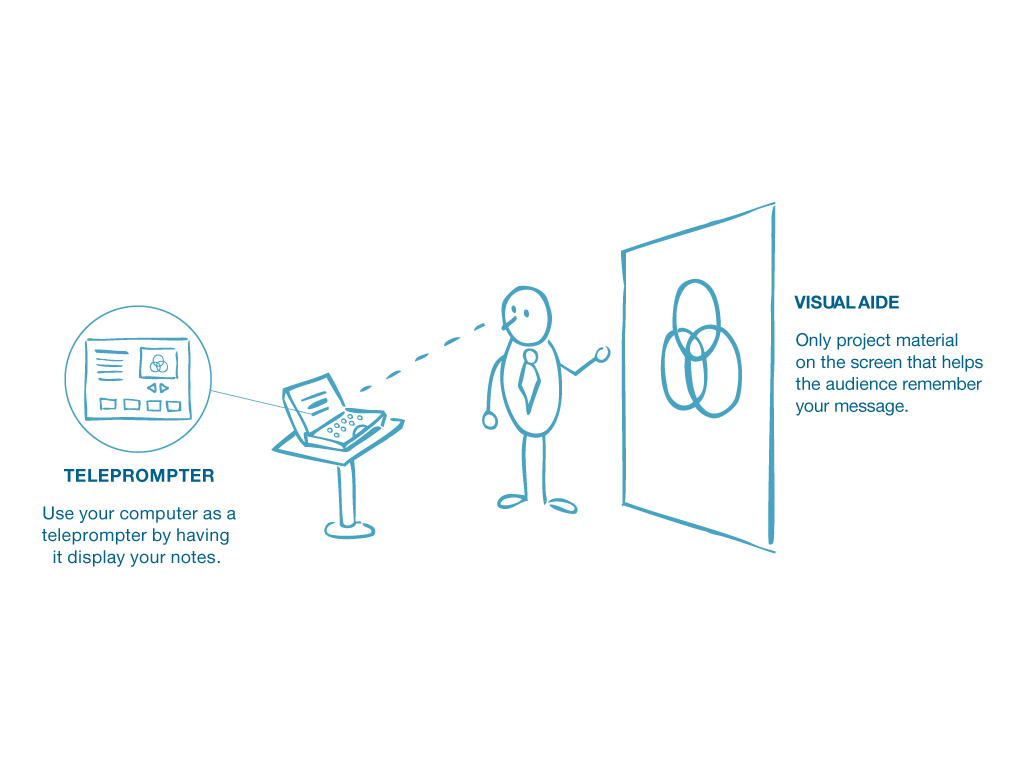

Your goal is to move away from projecting a document and toward giving a presentation. Reduce large phrases and bodies of copy to single words. Simplify the slides so the audience can process it in under three seconds. Remove as much from the slides as possible and move material into the notes. You can actually put as much information in the notes as you’d like.

Then, set up the slideshow to project the notes on the computer in front of you (Set Up Show / Show Presenter View). You can use the machine facing you as your teleprompter with all your notes in it, but behind you are projected clear, comprehensible slides for the audience. That way you won’t miss a beat!

After hearing the advice to remove as much as possible per slide, many react with, “But my boss wants each of her direct-reports to send in a five-slide overview of our initiatives and if I make sparse slides, she might not understand the progress we’ve made.” The boss is not asking for a presentation, she’s asking for a document. So cram as much as you need into that document to make it clear. There’s a time to be sparse-per-slide when you’re presenting and a time to be comprehensive-per-slide when submitting a document.

When slides are used appropriately, they work with the presenter seamlessly like a dance partner on the stage. One is coming and the other going, and each contributes to the other’s stage presence and craft.

Practice with your slides until you move as one with them.

Balance Emotion

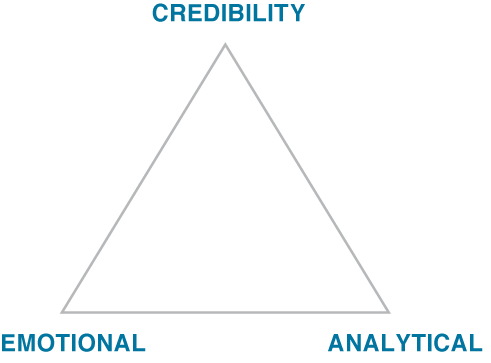

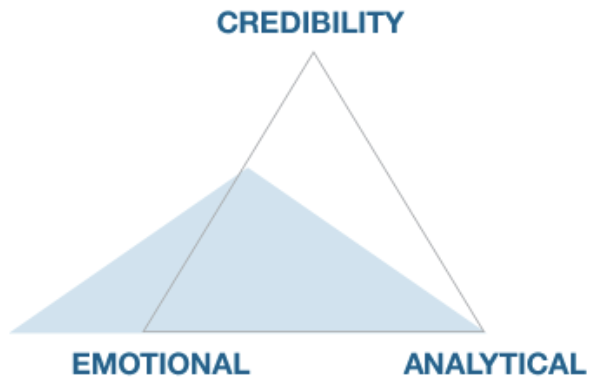

Persuasive presentations should appropriately balance analytical and emotional appeal.

Many pages in this book have been devoted to creating emotional appeal—not because it’s more important, but because it’s underused or non-existent, and should be incorporated. Now that your presentation has plenty of emotional appeal, let’s stay cognizant of its appropriate use.

Some topics are inherently emotionally charged—like gun control, racism, or abortion—and therefore naturally lend themselves to more emotional arguments. On the other hand, topics like science, engineering, finance, and academics inherently invite analytical appeals. But just because a presentation is more heavily weighted towards analytical content doesn’t mean it should be void of all emotion.

A question that comes up often is, “How much emotion should I use when presenting to a group of economists?” (You can replace the word economist with others like analysts, scientists, engineers, or researchers.) Some people choose their careers because of their analytical nature. If you know the audience has a career in a stereotypically analytical space, only a tiny percent of your appeal should be emotional—but do not leave emotion out entirely! At the very least, open and close your presentation with why. Many times the reason “why” people are involved in economics or science or engineering or research has an emotional component. Don’t strip it out, but don’t overdose on it either.

There’s another Greek word in the mix in addition to ethos, pathos, and logos. That word is karios. It means “timing” or “timeliness”—“speaking in the right moment, in the right way.” In order to do this, you must understand the situation, cross-check, and, if necessary, modify your presentation by adjusting its emotional and analytical balance so that it’s appropriate.

Keep in mind that all things in life should be done in moderation—including emotional appeal. Emotion should not be over amplified. If it is, the audience will feel manipulated. Appealing to emotion is only effective if it furthers the argument. Creating the right balance is alluring, whereas imbalance hurts your credibility.

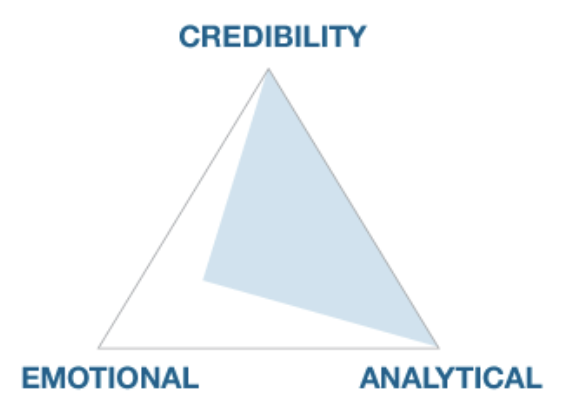

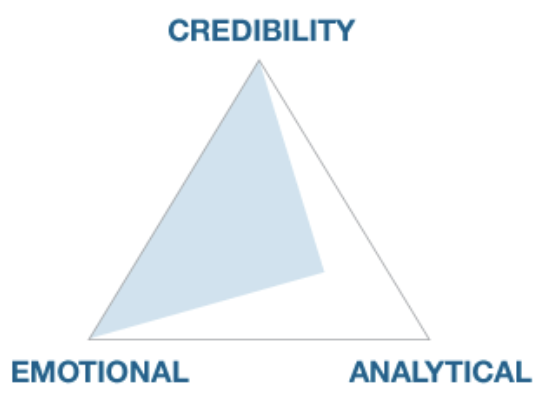

Instead of viewing the rhetorical triangle as something that is static and must be filled in to achieve perfect balance on all sides, consider it dynamic and alter the emotional appeal appropriately based on the situation. If you’re speaking to a broad audience on an emotionally charged topic, then don’t go through pages and pages of analytical research. Pull back on the brainy material. When speaking to a specialized audience in a narrowly analytical field, you need to emphasize analytical content. Notice in the far right triangle on the next page how imbalance will diminish your credibility.

Modify the presentation to map to the needs of the audience, increase or decrease the emotional and analytical to match the situation.

Highly analytical audiences do not like having their heartstrings tugged too much, if at all. They tend to interpret it as manipulation and an unnecessary waste of time. But these folks are human, and humans all care, like to laugh, and can be touched deeply. So, for example, including material in a presentation that shows how lives will be changed does motivate them, unless it’s presented in a melodramatic way.

Emotionally driven audiences don’t enjoy overuse of facts and details. They want to know that the details have been carefully considered, but probably don’t want to see twenty slides about them. They need a few proof points. A sales force might get more fired up about the incentive plan than diagrams explaining the complex innards of how a product ticks.

Taking the emotional or analytical appeal too far in either direction hurts your credibility. Even if you are the most qualified presenter in the world, being too geeky or too emotional can create a chasm between you and the audience.

Notice with the two triangles on the left, the credibility of the speaker stayed intact. That’s because these presentations hit the right balance for the audience.

Host a Screening with Honest Critics

We’ve become a first-draft culture. Write an e-mail. Send. Write a blog entry. Post. Write a presentation. Present. The art of crafting and then recrafting something well is disappearing in communications.

“The first draft of anything is shit.”

Ernest Hemingway

It’s easy for us to get attached to our own ideas, so it’s good to have another set of eyes and ears to review them. The best way to get feedback is to host a screening before you present to test your messages. The screening should filter out any meandering structure, obstructed messages, and confusing language.

Keep an open mind and come to the screening knowing that you will probably need to rework at least some percentage of the communication that you labored over for so long. No one ever hears during the first review, “I wouldn’t change a thing.” Regardless of how relentlessly you worked, there will be changes at this phase. The information was created from your perspective.

To the degree you are receptive to feedback from others you’ll be able to refine the receptivity potential of your material for others. The screening should influence and round out how you deliver your presentation.

Conway’s Law states, “Any organization that designs a system will inevitably produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.” In other words, the quality of the communication your organization generates is limited to the quality of the communication of the organization itself. For this reason, a presentation’s quality will not exceed the quality of the planning process that precedes it. Therefore, to pull together a team who will give you honest, quality feedback for the screening may require you to go outside of your organization to get quality feedback.

Remove yourself from a sugar-sweet or dysfunctional review environment. Instead, pull together a small group that has a similar profile as your target audience. They could be people in your industry like analysts, internal employees, trusted customers, or a focus group. Choose naysayers who will scrutinize, criticize, and challenge your perspective. You want them to be brutally honest when they tell you what they think.

Each screener should have a printout of the notes’ view of your presentation so they can quickly jot down thoughts on the words and the visuals. Run through the entire presentation once, and then revisit each section carefully. A solid review meeting should last about three times as long as the presentation itself. If your presentation is twenty minutes long, for example, each screening should take an hour. If your presentation lasts an hour, the screening should take three.

Give your test-audience a safe environment to tell you what they really think. Solicit feedback in a nondefensive way and let them challenge all assumptions. Encourage them to tell you if your presentation genuinely kept their interest.

Don’t ignore your screeners’ insights or give “yeah, but…” or “if they really knew…” excuses. Really listen to them, and incorporate their insights. Then, rework your material. Screening the presentation will remove any burrs that would unintentionally snag or poke the audience.

How to Deliver a TED-like Talk

The average presentation is forty-five minutes but a wonderful phenomenon is happening because of the influence of TED.com. TED is a conference that confines their presenters to 18 minutes. The good 18-minute talks go viral and spread ideas. Tight presentations are hard to do because all the key points need to be succinct in a short timeframe forcing the presenter to prepare. It’s easier to blather on for an hour than talk for a tight 18 minutes. At TED though, if you go over your allotted timeslot, you (literally) get the hook.

The culling process forces you to convey only the most important information for spreading your idea. The amount of rehearsal time is inversely proportionate to the length of the talk. The shorter the talk, the longer the rehearsal time. In this case, for an 18-minute talk, it could take up to 18 hours to rehearse. An hour a minute? That’s probably fair for someone who’s a professional presenter. A less seasoned speaker may need more!

I delivered a talk at TEDxEAST and was thrilled to look up at the clock just as it was ticking down with six seconds left. Victory! Then, I delivered a similar talk at the INK Conference in India but was restricted to only 15 minutes. I practiced like mad and timed it to a perfect 14 1/2 minutes, but the day of the presentation I was heavily medicated for a severe chest cold. I spoke from a fog, my time spread thin, and I got the dreaded “hook” because I ran one minute over. I would have run two minutes over if I hadn’t had step number three for creating a tight talk in place.

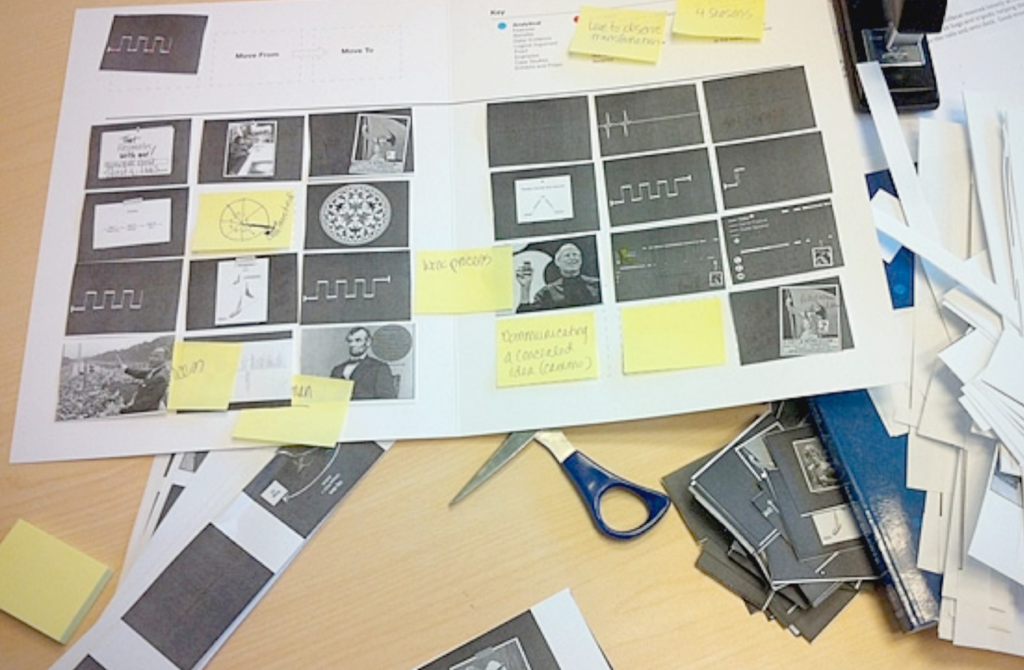

Here are the three steps for creating a tight talk:

ONE Print your current slide deck as 9-up handouts. The 9-up format is conveniently the same size as the smallest sticky note. Arrange and re-arrange your message and add sticky notes until you are happy with the flow. Make sure you cut at least one-third of the slides you use for an hour-long talk.

Trim and trim until you feel like it is close to 18 minutes. During this process it will be clear that your big idea could be communicated much more effectively than it had been. Assemble a handful of people you trust to give honest feedback on your mini-little-sticky-note slide deck. Verbally run the ideas by these folks—it doesn’t have to be a formal presentation. The purpose for having them look at all the little mini-slides at once is you want feedback on the “whole,” not the parts.

TWO Practice with clock counting up, then down. The first few times, rehearse with the clock counting up. That’s because if you go over, you need to know by how much. Do NOT be looking at the clock at this time. Have your coach look at it because you don’t want to remember any of the timestamps in your mind. Finish your entire talk and then have your coach tell you how much you need to trim. One minute, three minutes. Your coach should be able to tell you “trim 30 seconds here” or “add 15 seconds there” so that your content is weighted toward the most important information. Once you’re within 18 minutes, begin practicing with the clock counting down. You need to establish a few places in your talk where you benchmark a timestamp. Calculate roughly where you should be at six, twelve, and eighteen minutes. Know which slide you should be on and what you’re saying at each 6-minute moment so that you will know immediately from the stage if you’re on time or running over.

THREE Have two natural ending points. When I was getting the “wrap it up” signals from the show producers in India, I wanted to accuse the show operators of not really giving me a full 15 minutes on the clock. But I was the one who blew it. It might have been the medications I was on for my chest cold, but my timer was blinking 00:00 before I was done. Fortunately, I’d embedded two natural places to end my talk. I had an ending that made the talk complete and I stopped there. What I didn’t have time to get to was the inspirational ending that would have had the audience on their feet and screaming (well, they did end up on their feet, they just weren’t screaming).

Case Study: Leonard Bernstein

Young People's Concerts

Leonard Bernstein, Conductor, New York Philharmonic

Leonard Bernstein was a talented composer, conductor, pianist, teacher, and Emmy-winning television personality. He loved to talk about music, and did so with everyone: friends, colleagues, teachers, students, and even children. Bernstein’s unique intelligence and wit afforded him a reputation as music’s most articulate spokesperson.9

Variety magazine summed up his appeal by stating “The [New York] Philharmonic’s conductor has the knack of a teacher and the feel of a poet. The marvel of Bernstein is that he knows how to grab attention and carry it along, measuring just the right amount of new information to precede every climax.”10 Of all the things Bernstein accomplished, leading the Young People’s Concerts was one of his proudest legacies.

Several times a year, Carnegie Hall would fill with young children who came to learn about classical music. Bernstein would deliver a lecture-driven concert that could hold the attention of small children for an hour or more as he taught them complex music theory.

Bernstein’s explanations, analogies, and metaphors were delivered in a clear, simple, yet poetic presentation that consistently stayed at the children’s understanding level. He isolated various layers of the music, explained the theory behind it, played excerpts of it on the piano, and used various instrumentalists to play portions of it. Then, when the full piece was performed, the children had a clearer understanding of the many nuances.

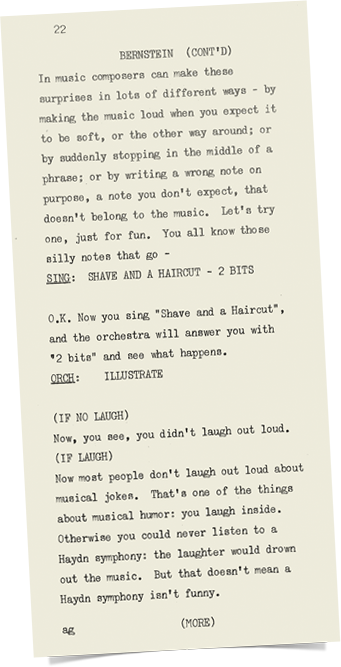

Below are three excerpts from one of the most difficult musical subjects to explain, “What is Symphonic Music?” Bernstein uses items familiar to the children as metaphors:11

- “How does development actually work? It happens in three main stages, like a three-stage rocket going into space. The first stage is the simple birth of the idea. Like a flower growing out of a seed. You all know the seed, for example, that Beethoven planted at the beginning of his [5th] symphony dunt dunt dunt duuuunt. Out of it rises a flower that goes like this: (plays piano)”

- “[Brahms] puts two to three melodies together…and takes scraps of melodies and turns things upside down like pancakes. But it’s not that it’s upside down but that it sounds amazing upside down. Will it be beautiful? That’s what makes Brahms so great. Music doesn’t just change, it changes beautifully.”

- “I’m hoping you’ll hear it with new ears and hear the symphonic wonders of it, the growth of it and the miracle of life in it that runs like blood through its veins and connects every note to every other note and makes it the great piece of music that it is.”

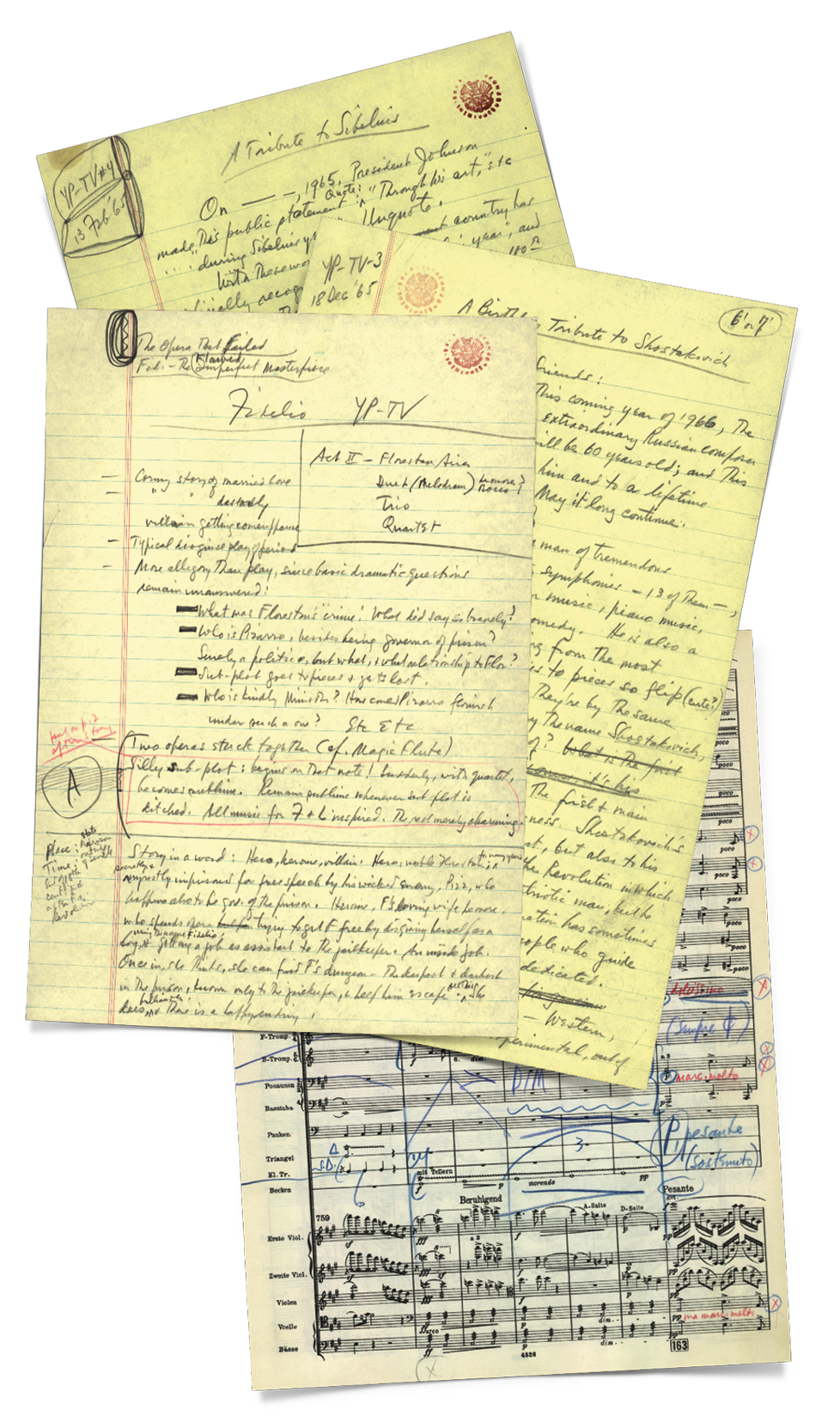

Bernstein worked for days on his Young People’s Concert scripts and rehearsed them several times so that when he was talking it would sound as if he were just having a calm, casual conversation with the children.

Few of Bernstein’s viewers were aware of how much dogged work went into his presentations. He was so adept at displaying an easy, casual manner that his presentations appeared to be born effortlessly and spontaneously. The truth, of course, was that he worked hard on his scripts. Weeks before, and right up to the last minute, his offices, house, and dressing rooms were filled with scattered piles of paper as he and his team wrote, planned, and rehearsed.12

Bernstein generated ideas on yellow legal pads and collaborated with his equally dedicated co-workers until a graceful, accessible script was formed.13 The team would make sure each metaphor and allegory was appropriate for the audience. Bernstein himself would walk through the script several times, marking and rehearsing as he went.

This excerpt from the script for “What is Classical Music?” shows how carefully Bernstein and his team planned.

Bernstein and his team edited constantly, right up to the moment he walked on stage. After each show, they would watch the recording of what he said and evaluate it to improve it the next time. He’d identify improvements he could make so he didn’t commit the same mistakes over and over. While all good conductors review their concerts, Bernstein applied this practice to his presentations as well, so that each one got better than the last.

Conductors are trained to have a disciplined rehearsal process, so editing a script through multiple iterations wouldn’t be a foreign process for them.

Bernstein tried to anticipate everything while he rehearsed and refined his presentation scripts. He planned every word and audience reaction carefully. He developed his scripts to the point of anticipating multiple audience responses—even writing alternate sections based on how people might react to the previous point. He even made notations of where and how he would stand while on the stage. The New York Philharmonic archives contain copies of scripts that show as many as ten revisions (in addition to the rounds on his yellow pads), which is a reflection of the thoroughness of Bernstein’s thought process and rehearsals.14

Bernstein wrote about his Young People’s Concerts experience in 1968 using words that can stand as his credo. “These concerts are not just concerts—not even in terms of the millions who view them at home,” he wrote. “They are, in some way, the quintessence of

all I try to do as a conductor, as a performing musician. There is a lurking didactic streak in me that turns every program I make into a discourse, whether I utter a word or not; my performing impulse has always been to share my feelings, or knowledge, or speculations about music—to provide thought, suggest historical perspective, encourage the intersection of musical lines. And from this point of view, the Young People’s Concerts are a dream come true, especially since the sharing is done with young people—that is, people who are eager, unprejudiced, curious, open, and enthusiastic.”15

Regardless of your subject matter, passion and practice make perfect.

Chapter 8 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.

In Summary

Practice makes perfect—kind of. An old adage says, “if anyone does not stumble in word, he is a perfect man.” And no one is perfect. There is always room to improve. So be tenacious in preparing yourself ahead of time. Rehearse and re-rehearse. Then afterward, solicit feedback—and if it was taped, review the recording and then start the refinement process all over again.

Successful people plan and prepare. To be successful in any profession requires discipline and mastery of skills. Applying that same discipline to the skill of communication will attach the audience to your idea and improve your professional trajectory.

Rule #8

Audience interest is directly proportionate to the presenter’s preparation.