9Change Your World

Changing the World Is Hard

“If you say, I have an idea for something,” what you really mean is, “I want to change the world in some way.” What is “the world” anyway? It is simply all of the ideas of all of our ancestors. Look around you. Your clothes, language, furniture, house, city, and nation all began as a vision in someone else’s mind. Your food, drink, vehicles, books, schools, entertainment, tools, and appliances all came from someone’s dissatisfaction with the world as they found it.1 Humans love to create. And creating starts with an idea that can change the world.

Staying passionate and tenacious about your idea requires that some part of you be uncomfortable with the status quo. At times, you must have enough resolve to put your reputation on the line for the sake of advancing your idea. It’s scary to go out on a limb and approach others with a product, philosophy, or ideal that you passionately support. Some will challenge it, and some will reject it. And that’s hard. Society doesn’t reward rejects, but it does reward those who have the tenacity to keep going after being rejected. So don’t give up.

My family collects large, vintage European posters. I love them because they all have one idea and one visual that clearly conveys the idea. Once, while we were on a family vacation, we visited one of our favorite poster dealers. Wearing white cotton gloves, he carefully showed us one table-sized poster after another. When he turned over a poster to reveal the one on the next page, my kids both gasped and said, “Oh my gosh, Mom, it’s you! You have to buy that poster.” Hmmm. I still can’t decide whether I think their reaction was a good thing.

This old French poster advertises baking spices. Baking spices! It’s humorous to see how fired up this gal is to promote her little collection of spices. But if I were to replace her pack of spices with the words “effective presentations,” I guess this is me. I get pretty fired up.

Ideas are not really alive if they are confined to only one person’s mind.

Your idea becomes alive when it is adopted by another person, then another, and another, until it reaches a tipping point and eventually obtains a groundswell of support.

President Kennedy gave a speech declaring that by the end of the decade, the United States should land a man on the moon and bring him home safely. He wanted support from every American. He said in the speech, “In a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon…it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.” He wanted the entire country to feel responsible for supporting his vision. Later in the 1960s, JFK was touring NASA headquarters and stopped to talk to a man with a mop. The President asked him, “What do you do?” The janitor replied, “I’m putting the first man on the moon, sir.” This janitor could have said, “I clean floors and empty trash.” Instead, he saw his role as part of the bigger mission that was to fulfill the vision of the President. As far as he was concerned, he was making history.2

“The only reason to give a speech is to change the world.”

John F. Kennedy

Use Presentations to Help Change the World

The world truly can be changed by presentations. No one could have imagined that a movie about a presentation would provoke change, generate global awareness, and even win an Academy Award. Former Vice President, Al Gore, had given his presentation hundreds of times to powerful audiences worldwide long before anyone had heard of An Inconvenient Truth. He was delivering a similar message way back in the 1970s, for instance.

While there might not be a need to change the whole world, you can certainly change your world by means of a presentation. The people featured in this book didn’t simply deliver their presentation one time and call it a day—they each delivered their presentation time and time again. They spent their lives communicating their vision over and over to many different audiences.

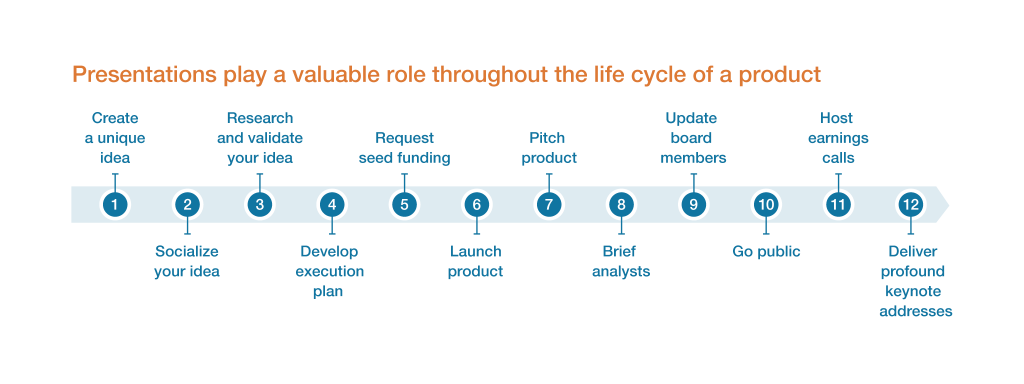

You may have to deliver your presentation multiple times in order to see a systematic adoption of your idea. Key communication milestones will become catalysts for your success throughout your journey to change the world. Each of these milestones is an opportunity to fine-tune your approach, pool resources, and realign the team. The ideas that are formulated during the brainstorming process have ample value—sometimes as much as the presentation itself.

“There is one thing stronger than all the armies in the world, and that is an idea whose time has come.”Victor Hugo3

Below are only a few of the milestones in a product launch that included a presentation. Each one represents a critical communication stage in the product’s life cycle that is usually conveyed through a presentation:

Remember, just because you communicated your idea once doesn’t mean you’re done. It takes several presentations delivered over and over to make an idea become reality. Well-prepared presentations will speed up the adoption and change your world!

Don't Use Presentations for Evil

Presentations should be used as vehicles for good, not evil—they are very powerful tools that can easily persuade. One glance at the hundreds of slides used as evidence in the Enron trial proves that presentations can play an obvious role in the perpetration of lies.

Counts against Jeff Skilling (Chief Executive Officer), Richard Causey (Chief Accounting Officer), and Kenneth Lay (Chairman of the Board) were all attributed to their presentations. Ken Lay was hit with two counts for employee presentations and each of the three was charged with 10 counts for their earnings call presentations. The Federal crime of wire fraud was also charged to Jeff, Ken, and Richard for the transmission of their presentations into various states via phones and web technology. On top of the charges mentioned, Skilling was sentenced to an additional fifty-two months for each of the five counts which he was convicted that involved presentations.5

Presentations got these executives into this mess, while the right presentation could have prevented it altogether.

- Scandal started with a presentation: Andrew Fastow, Enron’s Chief Financial Officer was the mastermind of clever accounting that used “special purpose entities” to hide billions of dollars and ultimately line his pockets with over $45 million dollars. According to USA Today, Fastow gave “a slick presentation on the LJM partnerships” (the organization created to hide debt) and the “Enron managers and analysts stared at each other in confusion. It sounded too good to be true.”6 A slick presentation

- Scandal could have been prevented with a presentation: A detailed presentation given by Arthur Anderson’s David Duncan in February 1999 feebly warned the Enron Board of Director’s audit committee of the company’s risky accounting

practices. This presentation could have saved Enron. If Duncan had boldly built a slide in capital letters saying “ENRON HAS RISKY PRACTICES THAT NEED INVESTIGATION,” its demise might have been avoided. Instead, Duncan’s notes found on the margin of his dense slide presentation said, “Obviously, we are on board with all of these (risks).”7

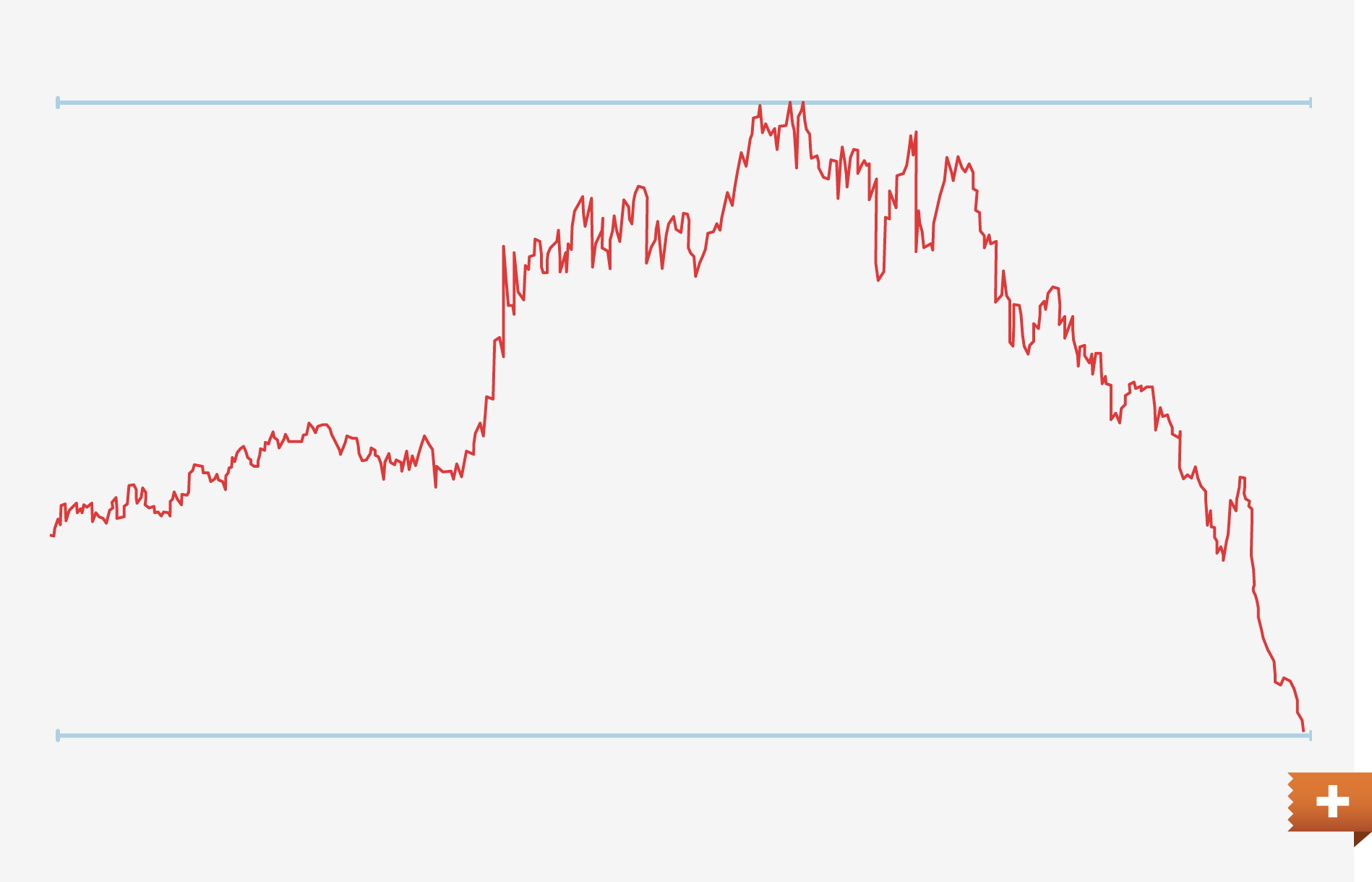

Enron’s top executives played by their own rules. They made risky bets motivated by greed and ambition. The collapse was inevitable. As masters of the PowerPoint chart, they showed upward projections for sales and profits, encouraging employees to invest while they themselves were frantically removing their own money. Employees who raised questions were mysteriously moved to other departments. Skilling distracted investors by proposing bold strategies for the next big score, like entering the broadband and weather futures markets. (What’s an oil company doing brokering weather anyway?)

They aggressively designed communication that abandoned reason and truth altogether, and used presentations as a propaganda device to spread lies to employees, analysts, and stockholders about Enron’s performance. In the ensuing collapse, the credibility of the board and the executives involved was obliterated, and tens of thousands of employees were financially ruined.

Oral communications have built and toppled kingdoms. Presentations are a powerfully persuasive medium that should be used to build up—not tear down.

Case Study: Martin Luther King, Jr.

His Dream Became Reality

Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of the greatest orators and civil rights activists in U.S. history. His goal was to end racial segregation and discrimination using peaceful means.

King delivered his electrifying “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington, which became the flash point for a movement.

Insights from “I Have a Dream”:

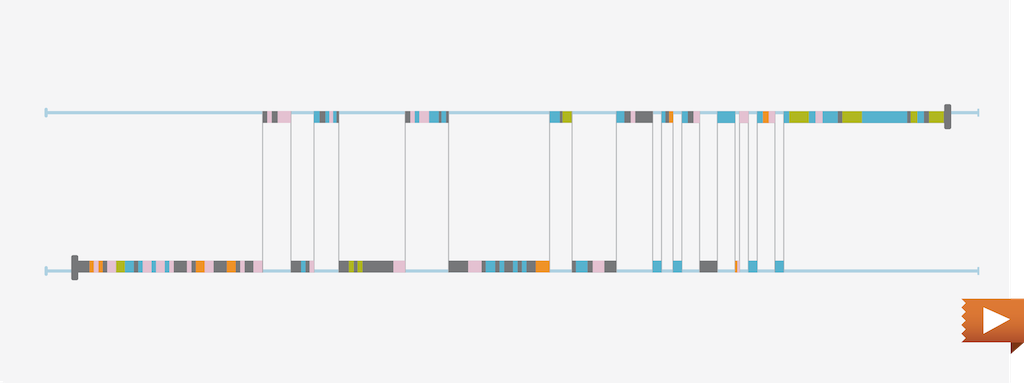

The sparkline on the next few spreads includes a full transcript of the speech to help identify the following insights:

- Contour: King’s speech moves between what is and what could be rapidly, which is an appropriate pace for the heightened energy of the gathering.

- Dramatic pauses: The transcript has a line break each time he pauses. As you’re reading it, breathe for a second or two at the end of each line to get a sense of how it was spoken.

- Repetition: King uses the rhetorical device of repetition often. Throughout the speech, he repeats word sequences to create emphasis. Toward the end, he repeats the phrase “I have a dream” several times, like the refrain of a hymn.

- Metaphor/visual words: King masterfully uses descriptive language to create images in the mind. For example, he states, “Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.”

- Familiar songs, Scripture, and literature: King establishes common ground by referencing many spiritual hymns and Scriptures familiar to the audience. He even rephrases a small sequence from Shakespeare: “This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn…”

- Political references: King pulls lines from several political resources like the United States Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, the United States Constitution, and the Gettysburg Address.

- Applause: There are varying degrees of applause throughout, ranging from clapping to clapping with loud cheering. In the sixteen-minute speech, the audience applauds twenty-seven times. That’s applause approximately every thirty-five seconds.

- Pacing: King speeds up and slows down to vary the quantity of words spoken per minute. This creates three distinct bursts or crescendos in his speech that build to the passionate ending that describes the new bliss.

King’s speech heightened the awareness of civil rights issues across the country, bringing more pressure on Congress to advance civil rights legislation and end racial segregation and discrimination.

In 1963, King was named Time magazine’s Man of the Year. A short forty-six years later, the United States elected its first African American President, Barack Obama.

Great communicators create movements.

Civil Rights Activist

MLK's Sparkline

Changing the world isn’t easy. Dr. King risked a lot for what he believed in. His house was bombed, he was stabbed with a letter opener and ultimately gave his life for his dream.

All of us are born with a dream to make the world a better place. Learning to communicate that dream is what will make the world a better place.

Be Transparent So People See Your Idea

You must be willing to be you, to be real, and to humbly expose your own heart if you want the people in the audience to open theirs. You must be transparent, and this is difficult. Standing in front of an audience is already a challenge in itself. When stage fright is compounded with the new demand on leaders to be transparent, it’s downright terrifying.

Being transparent moves your natural tendency of personal promotion out of the way so there’s more room for your idea to be noticed. The audience can see past you and see the idea.

There are three keys to being transparent:

- Be honest: Honesty means giving your audience the authentic you. It’s not honest when you portray yourself as a flawless, almighty, invincible, know-it-all. You’re not perfect, and your audience knows that. When you’re genuine and honest—both with yourself and them—there will be more moments of vulnerability and sincerity in your presentations and you’ll communicate your humanness.

It’s important to share stories that touch your listeners’ hearts, show how you have sometimes failed, and share ways you’ve overcome obstacles. Let people in to see that you’re real. Openly sharing moments of pain or pleasure endears you to the audience through transparency.

- Be unique: No two individuals have gone through exactly the same trials and triumphs in life. This means that you have collected stories and experienced feelings along the way that no one else can lay claim to. It’s those unique attributes that make you interesting. People often attempt to hide their differences so they can fit in better and be accepted, but it’s our unique perspective that can provide new insights to a situation or topic. Don’t hold back your ideas. It’s true that sometimes you’ll be the only person who is seeing what you see. Be okay with it!

- Don’t compromise: Speak forcefully and confidently about what you really believe in, and don’t back down. It’s a little frightening when your ideas are met with ridicule or rejection, but sometimes that’s the price of conviction. It’s never easy to attempt something that’s never been attempted before or speak up about a topic no one has the guts to confront. Take encouragement from the child in the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” When he had the guts to say what was really happening, he destroyed the pretenses of the entire royal court. Call it like it is.

Case Study: Martha Graham

Showed the World How She Felt

Martha Graham is recognized as a great innovator in dance, but she was an impressive communicator as well. She exemplifies characteristics that must be cultivated and nourished by any person who wants to become a great presenter. She made herself stand out by challenging the conventions of society. She persevered, even when confronted with obstacles that seemed overwhelming. She struggled with and conquered her fears. She respected her audiences, and established deep connections with them. And she never shied away from expressing her most profound feelings.

Graham spent her life challenging what dance is and what a dancer can do. She looked upon dance as an exploration, a celebration of life, and a religious calling that required absolute devotion.14

She succeeded in the world of dance against all odds. A career in dancing was frowned upon in the environment where she grew up.

By the time she began to seriously study dance, she was thought to be too old, too short, too heavy, and too homely for anyone in the profession to take her seriously.

“They thought I was good enough to be a teacher, but not a dancer,” she recalled. But she was determined and pursued dance with the intensity that was characteristic of everything she did in her life. Dance was her reason for living. Willing to risk everything, driven by a burning passion, she dedicated herself absolutely to her art. “I did not choose to be a dancer,” she often said. “I was chosen.”15

In Graham’s view, classical ballet was decadent and anti-democratic. After all, it was originally a spectacle created for royal European courts.

With its three hundred year tradition, it was a highly regimented form, graceful and precise, but not suited for freedom of expression.

Graham was prepared to abandon this tradition. In its place, she created a revolutionary new language of movement, a way of dancing that could express the joys, passions, and sorrows that are part of the human experience. She replaced traditional ballet’s soaring, graceful leaps with stark, angular movements, blunt gestures, and harsh facial expressions. Her goal was to express the primordial moods and feelings of humanity with dances intended to both challenge and disturb the audience.16

Graham’s revolutionary approach to dance was not well received by many—after all, it did not center on traditional beauty and romance. She was frequently ridiculed and made the butt of antagonistic jokes. Women’s suffrage had only recently arrived (in 1920),

and the rise of the “new woman” who could vote and pursue a career still made many people uncomfortable. A high-kicking, provocatively clad bevy of chorus girls was acceptable, but a dance company ran by a woman whose works were a comment on war, poverty, and intolerance seemed unnatural and aroused suspicion.17

She was protesting. Stark. And American. Many labeled her ugly, others called her revolutionary. But Graham was resolute in her desire to communicate how she felt.

“There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost.” Martha Graham

Dancer, Martha Graham Company

It was Graham’s belief that words could not always express the hidden emotional world made visible by dance.

Her goal was to create dances that would be “felt” rather than “understood.”18 She was often inspired by the ugly aspects of life and put them on display. All her dances had personal significance. They expressed fears and uncertainties that she herself had overcome.

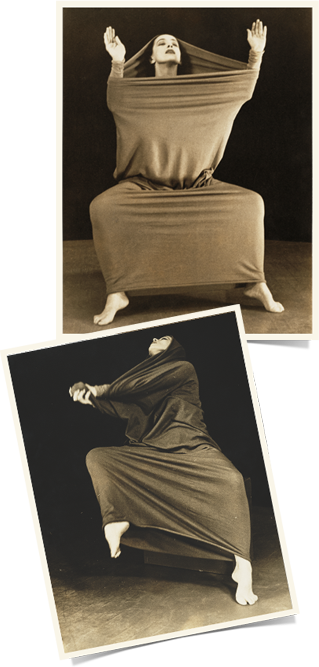

In 1930, Graham premiered a haunting solo dance of mourning called Lamentation. These rare photos show her sitting on a low bench, wearing a tube-like shroud with only her face, hands, and bare feet showing. In the dance, she began to rock with anguish from side to side, plunging her hands deep into the stretchy fabric, writhing, and twisting as if trying to break out of her own skin.

She was a figure of unbearable sorrow and grief. She did not dance about grief, but sought to be the very embodiment of grief.

Graham recalled, “One of the first times I performed it was in Brooklyn. A lady came back to me afterwards and looked at me. She was very white-faced and she’d obviously been crying. She said ‘you’ll never know what you have done for me tonight, thank you’ and left. I asked about her later and it seemed that she had seen her nine-year-old son killed in front of her by a truck. She had made every effort to cry, but was unable to.

But when she saw Lamentation she said she felt that grief was honorable and universal and that she should not be ashamed of crying for her son. I remember that story as a deep story in my life that made me realize that there is always one person to whom you speak in the audience. One.”19

Graham moved in a way that gave anger and grief back to her audiences. She had a genius for connecting movement with emotion. She could make visible all those feelings that people have inside them, but can’t put to words.

No matter what the medium, communication is hard work, and this was true of Graham’s dances. When the concept for a new dance was in its early stages, it was “a time of great misery.” Propped up in her bed, she often worked into the late hours, jotting down thoughts, impressions, even quotations from books—

whatever she could find to nourish her imagination.

“I would put a typewriter on a little table on my bed,

bolster myself with pillows, and write all night.”20

She read widely as she searched for ideas and inspiration, studying psychology, yoga, poetry, Greek myths, and the Bible. Gradually, the ideas that filled her notebooks would begin to reveal a pattern, and she would write out a detailed script.21

Graham’s work again and again portrays situations where a woman is called to a high purpose, but is unable to answer that call until she overcomes her fear. This is how Graham saw herself. She said she had been given “lonely, terrifying gifts” that could be seen almost as a divine command to plumb the depths of the human spirit, no matter what comfortless truths might be found there.22

She was asked by the U.S. government to become a cultural ambassador in 1955 and tour major cities in seven countries. She lectured in every city, but speaking made her nervous. Agnes de Mille describes one scene in her biography, Martha. “She hung onto the barre, clung to the walls. She couldn’t think what to do with her hands, with her robes, with her feet.” Finally, she escaped into her dressing room and locked the door.23 Through repeated effort, Graham conquered her fear and went on to become what State Department officials called “the greatest single ambassador we have ever sent to Asia.”24

Until she was 90, Graham continued to deliver lectures, which she had developed into an art form. A striking figure with a seductive voice, poetic insights, and a faultless sense of timing, she learned how to hold an audience spellbound.25

You could say that by trying to discover herself, she founded the world of modern dance. During her long journey, she invented a new way of moving, a unique dance language that has thrilled audiences all over the world and enlarged our understanding of what it means to be human.26

All of us are unique. We each have our own pattern of creativity, and if we do not express it, it is lost for all time.

Graham challenged the conventions of dance and overcame every obstacle so she could present new ideas. Some loved her, and some reviled her, but she persisted in overcoming her fears to express the feelings in her soul. Her commitment to expressing her feelings transformed dance forever.

You Can Transform Your World

Whether your opportunity to convey your passion comes through work or other activities, there will be a moment in your life when making an idea clear will play a significant role in shaping who you become—and the legacy you leave behind.

Your ideas may be simple, or could contain the keys that unlock unknown mysteries. However, if you don’t communicate them well, they will lose their value and add nothing to humanity.

The amount of value you place on your idea should be reflected in the amount of care you take in communicating it.

Passion for your idea should drive you to invest in its communication.

We have examined many people whose presentations altered the status quo throughout this book. Through their presentations they were able to charm the world and make it a better place. These presenters are each unique—stemming from different faiths, backgrounds, and passions; yet each one of them chose to invest in effective communication by which they changed the world. Upon examination of the deep impact they’ve each had, you can easily tell yourself that you could never live up to their example because they were born to present and it doesn’t come as naturally to you. Poor excuse—that just isn’t true.

Great presenters are created—they invest hundreds of hours into their presentations including each word, structure, and the delivery of their idea. The people’s presentations featured in this book did not come easily to them, but they dedicated themselves to delivering their idea in a manner that was effectively persuasive. Some even risked their lives for their ideas.

If you aren’t inspired by what you do — or if you don’t have a message to convey that you’re passionate about — find your calling. This book looked at a motivator, a marketer, a politician, a conductor, a lecturer, a preacher, an executive, an activist, and an artist. They all had their own well of inspirational ideas and their own unique way of communicating them. You can too. You just need to find what inspires passion in you. Then you must apply the same discipline to communicating it as musicians or dancers apply to their craft.

Nowadays, more than any other time, people are eager for inspired ideas that stand out and are worth believing in. There’s so much disingenuous noise in our culture that when an idea is presented with sincerity and passion, it stands out and resonates.

We were born to create ideas; getting people to feel like they have a stake in what we believe is the hard part. It’s not fair that an idea’s worth is judged by how well it’s presented, but it happens every day.

You never forget

a good story

Stories stick with us — beyond bedtime, and beyond the boardroom. The Duarte Studio’s team of writers and designers work with you to synthesize and visualize your message into a memorable presentation designed to shift audience beliefs and behaviors.

Have questions? Reach out.

info@duarte.com/650.625.8200

www.duarte.com

Learn from

our experience

Our workshops bring to life the principles from our books, gleaned from more than two decades of presentation experience. Leave the workshop with immediately applicable skills, and a new approach to presentations.

Have questions? Reach out.

academy@duarte.com/650.625.8200

www.duarte.com

Chapter 9 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.