1Why Resonate?

Persuasion Is Powerful

Movements are started, products are purchased, philosophies are adopted, subject matter is mastered—all with the help of presentations.

Great presenters transform audiences. Truly great communicators make it look easy as they lure audiences to adopt their ideas and take action. This isn’t something that just happens automatically; it comes at the price of long and thoughtful hours spent constructing messages that resonate deeply and elicit empathy.

Throughout the book you’ll learn from some of the greatest communicators. Each is different and yields a unique insight, yet they share a common thread: they all create a groundswell of support for their ideas. These communicators don’t have to force or command their audiences to adopt their ideas. Instead, the audience responds willingly with a surge of support.

ACTIVIST

Martin Luther King, Jr.,

Civil Rights Activist

Great Communicators

ARTIST

Martha Graham,

Contemporary Dancer

CONDUCTOR

Leonard Bernstein,

Conductor,

New York Philharmonic

Orchestra

EXECUTIVE

Steve Jobs,

Chief Executive Officer,

Apple Inc.

LECTURER

Richard Feynman,

Professor,

California Institute of Technology

MARKETER

Beth Comstock,

Chief Marketing Officer,

General Electric

NEGOTIATOR

Jawaharlal Nehru,

Prime Minister,

India

PREACHER

John Ortberg,

Pastor,

Menlo Park

Presbyterian Church

POLITICIAN

Ronald Reagan,

Former President

of the United States

Resonance Causes Change

Presentations are most commonly delivered to persuade an audience to change their minds or behavior. Presenting ideas can either evoke puzzled stares or frenzied enthusiasm, which is determined by how well the message is delivered and how well it resonates with the audience. After a successful presentation, you might hear people say, “Wow, what she said really resonated with me.”

But what does it mean to truly resonate with someone?

Resonance is a well-known phenomenon in physics. You can cause an object to vibrate without any physical contact—if you know its natural rate of vibration. When an object responds to an external stimulus that has the same frequency as its own, that’s resonance. The video you see here is a beautiful visual illustration of resonance. My son connected a metal plate to an amplifier so that the sound waves would travel through the plate. Then he poured salt onto it. As he raised the frequency, the sound waves tightened and the

grains of salt jiggled, popped, and then moved to new places, reorganizing themselves into beautiful patterns as though they knew where they “belonged.” Haven’t you often wished you could make customers, employees, investors, or students snap, crackle, pop, and move to the new place they need to be in order to create a new future?

Wouldn’t it be great if audiences were as obedient and united in thought and intent as the grains of salt? They can be. If you tune yourself to the frequency of your audience, your ideas will resonate deeply, and your audience will demonstrate self-organizing behavior. Your listeners will understand where they must move to collectively form something beautiful: a groundswell.

The audience does not need to tune themselves to you—you need to tune your message to fit them. Skilled presenting requires you to understand their hearts and minds and create a message to resonate with what’s already there. Your audience will be significantly moved if you send a message that is tuned to their needs and desires. They might even quiver with enthusiasm and act in concert to create beautiful results.

Change Is Healthy

Presentations are about change. Businesses, and indeed all professions, have to change and adapt in order to stay alive.

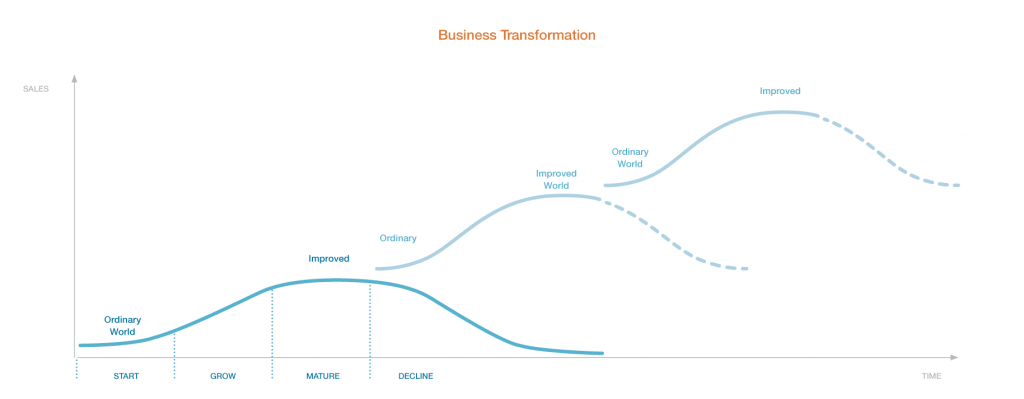

Organizations pass through a life cycle from start-up to growth to maturity—and eventually to decline—unless they work to reinvent themselves. Businesses are usually founded because someone had a clear vision of a future world that was an improved place. But that improved world of tomorrow quickly becomes the ordinary world of today. When an organization reaches maturity, it shouldn’t get too comfortable or it will decline. To avoid that, it must change strategy so it can continue to be at the right place at the right time in the new future. Otherwise, it will eventually wither. Each strategy change in the reinvention process must be communicated to all the stakeholders, both internal and external.

Moving in the direction of an uncertain future with unknown risks and rewards takes guts and intuitive skill, yet unless businesses make these moves they’re not likely to survive. Companies that are able to flourish in the never-ending alternation and tension between what is and what could be are healthier than companies that can’t. It’s often impossible to quantify the future based on statistics or make predictions that have the trustworthiness of proven facts. Leaders must sometimes follow their gut into uncharted regions where no statistics have ever been generated.

Organizations must continually shift and make improvements to remain in good health. That converts even the most ordinary presentations at staff meetings into platforms for persuasion. Your team needs to be motivated to self-organize at new, specific places in the future to avoid the possible demise of your organization.

Getting ahead of the next curve requires courage and communication: courage to determine the next bold move, and communication to keep the troops committed to the value of moving forward.

Rallying stakeholders to move together in a common course of action is all part of the innovation and survival process. Leaders at every level in an organization need to be skillful at creating resonance if that organization is to control its own destiny.

“Progress is impossible without change; and

those who cannot change their minds cannot

change anything.”

George Bernard Shaw

Presentations Are Boring

Presentations have become the common language of business activity because no other communication tool is as effective for transforming an audience—yet many presentations are boring. Most fail dreadfully as communication tools, and the rest are just not interesting. How could these corpses be resuscitated to the point that they not only show signs of life, but actually engage audiences and evoke rapt attention?

If you’ve been trapped in a bad presentation, you recognize the feeling almost immediately. You can tell within minutes that it’s just not good; it doesn’t take long to recognize a corpse! To make matters worse, it’s becoming more and more difficult to keep an audience’s attention as global cultures become media-rich environments.

So why then, if presentations are so bad, are they scheduled? People inherently know that connecting in person can yield powerful outcomes. We crave human connection. Throughout history, presenter-to-audience exchanges have rallied revolutions, spread innovation, and spawned movements. Presentations create a catalyst for meaningful change by using human contact in a way that no other medium can.

Many times it isn’t until you speak with people in person that you can establish a visceral connection that motivates them to adopt your idea. That connection is why average ideas sometimes get traction and brilliant ideas die—it all comes down to how the ideas are presented.

To move closer to the pulse of entertainment, presentations must have an ebb and flow, and what provides that movement is contrast—in content, texture, and delivery. Just like you tap your toe to a good beat, your brain enjoys tapping along with a good presentation, but only if something new is continually unfolding and developing.

Breathing life into an idea requires a lot of effort. Creating a presentation that’s interesting is a thoughtful process that involves a lot more than simply throwing together the kind of blather that we’ve come to call a presentation. You have to make a serious commitment to the time, discipline, and energy it takes to understand your audience and craft a message that will resonate with them.

There is a simple way to determine whether it’s worth putting this level of commitment into a presentation…

Just ask yourself:

How badly do I want

my idea to live?

The Bland Leading the Bland

The presenter’s job is to make the audience clearly “see” ideas. If your ideas stand out, they’ll be noticed. The enemy of persuasion is obscurity. You can learn what attracts attention by examining the opposite—camouflage. The purpose of camouflage is to reduce the odds that someone will notice you by blending into an environment. When is blending in appropriate for a communicator? Never. The more you want your idea adopted, the more it must stand out. If the idea blends with the environment, both its clarity and chances for adoption are diminished. An audience should never be asked to make decisions based on unclear options.

Don’t blend in; instead, clash with your environment. Stand out. Be uniquely different. That’s what will draw attention to your ideas. Nothing has intrinsic attention-grabbing power in itself. The power lies in how much something stands out from its context.

If you go hunting with your college buddies and don’t want to be confused with their prey, you’d be advised to wear safety orange. Since there’s nothing in the woods that particular color, you’ll stand out.

In communications, standing out from the “environment” means standing out amongst your competitors or even contrasting within your own organization. You must show how your idea contrasts with existing expectations, beliefs, feelings, or attitudes if you want to gain the audience’s rapt attention. It certainly feels safer and easier to conform to the well-worn groove of sameness than to stand out and be vulnerable. But being buried in a sea of sameness does not yield greatness or solve big problems.

It can be scary running around your bland organization with a safety orange target on your back. It’s risky, and it takes fortitude to be different amongst friend and foe. But it’s important for your message to stand out, or it won’t be remembered.

While you don’t necessarily need to rebel against the current messages and content, you do need to lift them out of the drab traditional way they are communicated. Identify opportunities for contrast and then create fascination and passion around these contrasts.

Presentations today are boring because there is nothing interesting happening. They have no contrast and hence, interest is lost.

People Are Interesting

There’s truth in the cliché, “Just be yourself.” Showing your humanness when you present is a great way to stand out. It’s a quality that’s totally lacking in most presentations today—even though the entire audience consists of humans! In many organizations, employees are conditioned to string together meaningless words, put them on slides, and then repeat them like a robot. The accepted norm is for presenters to hide behind slides, as though hiding were a form of effective communication.

Presenters think they can hide behind a wall of jargon, but what people are really looking for when they sit down at a presentation is some kind of human connection.

When two people share common beliefs and connect based on those beliefs, the result is the most human, transparent, and relational form of communication that can occur. Presentations are ideal opportunities for this level of communication, because they are one of the few types of interactions where people connect in person, and it’s deep connections that make great presentations stand out. Forming connections is an art, and when it’s practiced well, the results can be astounding.

Being human and taking risks are the foundation of creative results. Taking risks shows you’re willing to tap into something your gut is telling you will work, and then not letting your head talk you out of it. That’s creativity and humanness at its best. Unfortunately, many cultures stifle risk-taking, and many workplaces constrain human connectedness.

“Being true to yourself involves showing and sharing emotion. The spirit that motivates most great storytellers is ‘I want you to feel what I feel,’ and the effective narrative is designed to make this happen. That’s how the information is bound to the experience and rendered unforgettable.”

Peter Guber1

It’s easier to rattle off jargon and keep communication emotionally neutral. But easiest doesn’t always mean best.

These statements are from real presentations that have had all the humanness sucked out of them. It’s easier to hide behind messages like these instead of tapping into what is human about us.

Facts Alone Fall Short

Even with mountains of facts, you can still fail to resonate. That’s because resonance doesn’t come from the information itself, but rather from the emotional impact of that information. This doesn’t mean that you should abandon facts entirely. Use plenty of facts, but accompany them with emotional appeal.

There’s a difference between being convinced with logic and believing with personal conviction. Your audience may agree with the thought process you present, but they still might not respond to the call. People rarely act by reason alone. You need to tap into other deeply seated desires and beliefs in order to be persuasive. You need a small thorn that is sharper than fact to prick their hearts. That thorn is emotion.

“The problem is this: no spreadsheet, no bibliography and no list of resources is sufficient proof to someone who chooses not to believe. The skeptic will always find a reason, even if it’s one the rest of us don’t think is a good one. Relying too much on proof distracts you from the real mission—which is emotional connection.”

Seth Godin2

So today more than ever, communicating only the detailed specifications or functional overviews of a product isn’t enough. If two products have the same features, the one that appeals to an emotional need will be chosen.

Aristotle said that the man who is in command of persuasion must be able “to understand the emotions—that is, to name them and describe them, to know their causes and the way in which they are excited.” And that “persuasion may come through the hearers, when the speech stirs their emotions.”3

As consumers, people are hardly strangers to emotional appeal, and there’s little doubt that they’re prepared to respond emotionally to a presentation. So why aren’t presentations more emotional? The answer is, it’s an uncomfortable style for presenters, and especially for analytical professionals. At work, most people think, “They’re not paying me to feel, they’re paying me to do.” Of course that’s true. But if you can’t motivate your team to move forward or convince your customers to buy, then you are in trouble.

Including emotion in a presentation doesn’t mean it should be half fact and half emotion. It also doesn’t mean there should be boxes of tissue under each seat. It simply means that you introduce humanness that appeals to the desires of the audience. It’s not that difficult to evoke a visceral reaction in an audience if you use stories.

“The public is composed of numerous groups that cry out to us: ‘Comfort me.’ ‘Amuse me.’ ‘Touch my sympathies.’ ‘Make me sad.’ ‘Make me dream.’ ‘Make me laugh.’ ‘Make me shiver.’ ‘Make me weep.’ ‘Make me think.’”

Henri René Albert Guy De Maupassant4

Stories Convey Meaning

Ever since humans first sat around the campfire, stories have been told to create emotional connections. Stories have also served as containers of information. In many societies, they have been passed along nearly unchanged for generations. The greatest stories of all time were packaged and transferred so well that hundreds of illiterate generations could repeat them. Our early ancestors had stories to explain day-to-day occurrences in nature like why the sun rises and falls, as well as more overarching, meta-narratives about the meaning of life. Stories are the most powerful delivery tool for information, more powerful and enduring than any other art form.

People love stories because life is full of adventure and we’re hard-wired to learn lessons from observing change in others. Life is messy, so we empathize with characters who have real-life challenges similar to the ones we face. When we listen to a story, the chemicals in our body change and our mind becomes transfixed.5 We are riveted when a character encounters a situation that involves risks and elated when he averts danger and is rewarded.

If you’re like many professionals, using stories to create emotional appeal feels unnatural because it requires showing at least some degree of vulnerability to people you don’t personally know all that well. Telling a personal story can be especially daunting because great personal stories have a conflict or complication that exposes your humanness or flaws. But these are also the stories that have the most inherent power to change others. People enjoy following a leader who has survived personal challenges and can share her narrative of struggle and victory (or defeat) comfortably.

Stories Convey Meaning

“The best way to unite an idea with an emotion is by telling a compelling story. In a story, you not only weave a lot of information into the telling but you also arouse your listener’s emotions and energy. Persuading with a story is hard. Any intelligent person can sit down and make lists. It takes rationality but little creativity to design an argument using conventional rhetoric. But it demands vivid insight and storytelling skill to present an idea that packs enough emotional power to be memorable. If you can harness imagination and the principles of a well-told story, then you get people rising to their feet amid thunderous applause instead of yawning and ignoring you.”

Robert McKee6

Information is static; stories are dynamic—they help an audience visualize what you do or what you believe. Tell a story and people will be more engaged and receptive to the ideas you are communicating. Stories link one person’s heart to another. Values, beliefs, and norms become intertwined. When this happens, your idea can more readily manifest as reality in their minds.

You Are Not the Hero

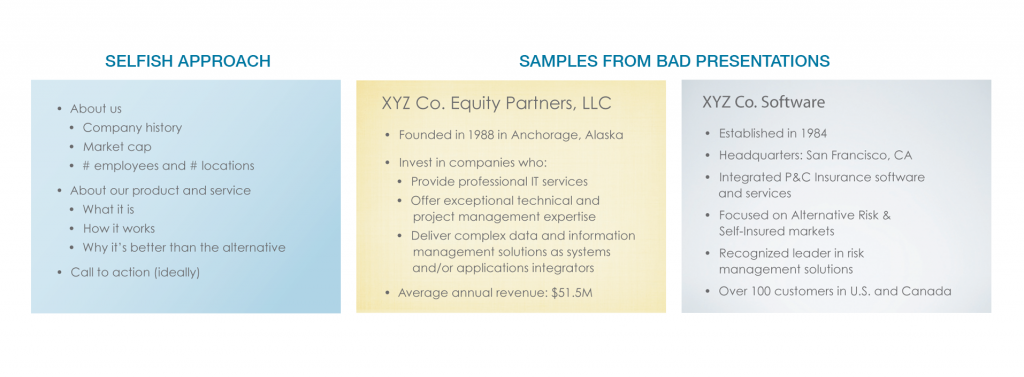

Whether you’re trying to connect with your audience through stories or some other way, you must remember that your presentation isn’t all about you. Audiences react very badly to arrogance and ego. These traits call up the same feelings you’ve probably had when you find yourself cornered by some dreadful, self-centered know-it-all at a cocktail party. He’ll tell you about what he is interested in, how hip he is, and imply that you are lucky to have met him. Meanwhile you’re thinking, “What an asshole!” and searching for any chance to escape. Why is that? It’s because his monolog doesn’t include you, your thoughts, or your point of view. Self-focused people don’t make connections. No one wants to date, work with, or sit through a presentation given by someone like that. So why is it that presentations are so packed with self-centered content?

Most presentations start with “me-ness.” Somewhere in the front of the slide deck is the dreaded “it’s all about me” slide that typically looks like one of the slides below.

It is important that the audience know something about you and your company. There are ways to communicate this information (like a handout) so you can focus on the people in the audience right at the onset and focus your presentation so it resonates at their frequency instead of yours.

When you present, it’s natural to believe your product or cause should be more important than anything else to your audience. You may even feel like you’re their hero, there to rescue them from their helplessness and ignorance. You may think, “If they only knew what I know, the world would be a better place.” But if you get up in front of them and rattle on about yourself, your ideas, and your products, you’ll be just like the self-centered jerk at the cocktail party, and your audience will want to flee.

Instead, embrace a stance of humility and deference to your audience’s needs. Begin the presentation from a shared place of understanding. Make it about the audience.

The Audience Is the Hero

You need to defer to your audience because if they don’t engage and believe in your message, you are the one who loses. Without their help, your idea will fail.

You are not the hero who will save the audience; the audience is your hero.

Screenwriter Chad Hodge points out in Harvard Business Review that we should “[help] people to see themselves as the hero of the story, whether the plot involves beating the bad guys or achieving some great business objective. Everyone wants to be a star, or at least to feel that the story is talking to or about him personally.”7 Business leaders need to take this to heart, place the people in the audience at the center of the action, and make them feel that the presentation is addressing them personally.

When you show up to give a presentation, your attitude shouldn’t be an arrogant, “It’s all about me.” Instead, it should be a humble, “It’s all about them.” Remember, your success—and the success of your firm—both depend on them, not the other way around. You need them.

If you’re asking yourself, “What’s my role?” the answer is, you’re the mentor. You’re not Luke Skywalker. You’re Yoda. It’s the audience that’s going to do all the hard work so that you can attain your objectives. You’re just a voice that can help them get unstuck on their journey.

Mentors are usually depicted as sources of wisdom. Modern examples of mentors are The Oracle in The Matrix or Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid. As a mentor, your task is to support the hero with guidance, insight, training and advice, instill confidence, and even provide magical gifts so he can get past his fears and begin a new journey with you.

If you alter your stance from seeing yourself as the hero to accepting the role of mentor, your viewpoint will change. You’ll feel more humility as your audience’s aide de camp. Remember, the nature of a mentor is to be selfless and willing to make personal sacrifices to help the hero obtain his reward.

Most mentors have the experience to teach others about the journey because they were once heroes themselves. They can share the knowledge they gained about special tools and powers they picked up on their own life’s journey. Mentors have traveled the hero’s road before and they can pass on the skills they acquired to the hero.

You may well be the smartest person in the room where you’re giving your presentation, but you must wield the power that knowledge gives you wisely and humbly. You should never view a presentation as a chance to show how brilliant you are. You want the audience to leave thinking, “Wow, spending time in that presentation with (your name goes here) was a true gift. I’m armed with insights and tools to help me succeed that I didn’t have before.”

Changing your stance from hero to mentor will clothe you in humility and help you see things from a new perspective. Audience insights and resonance can only occur when a presenter takes a stance of humility.

Chapter 1 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.

In Summary

Presentations have the power to change the world. The nexus of almost every movement and high-stakes decision relies on the spoken word to get traction, and presentations are a powerful platform to persuade.

But presentations are broken; they are considered a necessary evil instead of a tool of great power. That power springs from the presenter’s ability to make a deep human connection with others. Instead of connecting with others, presentations tend to be self-centered, which alienates audiences. The opportunity to transform is diminished when audiences don’t feel a connection.

Changing your stance from that of the hero to one of the wise storyteller will connect the audience to your idea, and an audience connected to your idea will change.

Rule #1

Resonance causes change.