3Get to Know the Hero

How Do You Resonate with These Folks?

It’s official: The guidance you got from your high school speech teacher, to imagine the audience in their underwear, is now obsolete. Instead, you should imagine them wearing bright stockings and tunics emblazoned with superhero emblems—because the people in the audience are the heroes who will bring your big idea to fruition.

To genuinely connect with your audience, you need to know what makes them tick. What strikes them as funny? What makes them sad? What unites them? What will cause them to rise up and act? What is it that makes them deserve to win in life? So how do you get to know them and really understand what their lives are like? It’s important to figure this out because according to the former AT&T presentation research manager, Ken Hamer,

“Designing a presentation without an audience in mind is like writing a love letter and addressing it ‘to whom it may concern.’”1

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to build empathy for your audience by exploring the elements of the hero and mentor archetypes.

Though your heroes might be lumped together in a room, you shouldn’t view them as a homogeneous blob. Instead of thinking about the audience as a unified clump when preparing your presentation, imagine them as a line of individuals waiting to have face-to-face conversations with you.

You want to make each person feel like you’re having a personal exchange with him or her; it will help you speak in a conversational tone, which will keep them interested. People don’t fall asleep during conversations (unless your conversations are boring, too. If so, you need help beyond what this book provides).

An audience is a temporary assembly of individuals who, for an hour or so, share one thing in common: your presentation. They are all listening to the same message at the same moment; yet all of them are filtering it differently and gleaning their own unique insights, points of emphasis, and meaning. If you find common ground from which to communicate, their filter will more readily accept your perspective.

You need to get to know these folks. You are their mentor! Each one has unique skills, vulnerabilities, and even a nemesis or two. The audience must be your focus while you create the content of your presentation. They are so important, in fact, that the next two sections of the book will revolve around the audience. So, stop thinking about yourself, and start thinking about connecting with them.

Segment the Audience

One way to get to know your audience is through a process called segmentation. By partitioning a large audience into smaller sub-segments, you can target the segment that will bring the most additional supporters. Determine which group is most likely to adopt your perspective—the group where you can make the greatest impact with the least effort. It’s tricky to appeal to the broader audience and simultaneously connect deeply with the subset that will play a key role in helping you—but it’s worth the effort.

The most commonly used segmentation method is to segment by demographics. Most conference organizers can provide only limited information about the audience: where they work, their title, geographical location, and company. You can make some assumptions from this information, but it’s limited to just that—assumptions.

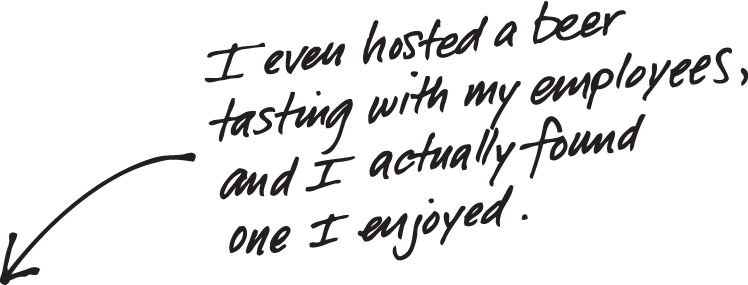

When I presented to top executives from a national beer manufacturer, I needed to spend time thinking about how to connect with them, because based on demographics alone, we did not have much in common in this arena.

I’m a middle-aged female who drinks fruity cocktails because I imagine beer might taste like fizzy pee. That’s a pretty big gap.

I didn’t receive enough information from the event organizers to feel like I really knew what’s important to them.

| BEER Executive |

Nancy Duarte | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 34 Males, 14 Females |

Female |

| Job Title | Executives with titles like director, vice president, and CMO |

Entrepreneur and CEO |

| Geography | They flew in from 11 countries |

I drove 3.6 miles up the road |

Collecting their gender and country of origin isn’t enough information to communicate with them meaningfully. Audiences aren’t moved solely because they are old or young, from Kansas or California. Their demographics are only part of the story.

Truly communicating effectively takes research. That can mean sending out your own survey that will help you gain insights or—if you’re targeting a broader industry group—going online and finding popular blogs by industry icons to see what’s on their minds. You might take note of what they chat about on social media sites until you reach a point where you feel you know them personally.

Don’t segment the audience in a clichéd or generalized way. Defining your audience too broadly can make you seem impersonal or unprepared. It can cause your audience to feel like a statistic, or like they are being narrowly stereotyped, which can be offensive. The main idea is that you need to define the audience in a way that’s accurate and appropriate for the kind of presentation you will deliver.

Several things helped me to prepare for the presentation to the beer executives. I bought subscriptions to a couple of key marketing publications to see what was being said about their brands, solicited feedback from my social network, searched for articles about them, reviewed their conversations in the top beer blogs, found their own presentations on the web, read their press releases, and read their company’s latest annual report. I even had my company do a bit of market research to surface the nuances among the various products.

The research helped me understand their challenges. Even though I only used a portion of the insights in the actual presentation, I felt like I knew them and had empathy for what was on their minds. Those insights helped me feel connected to them.

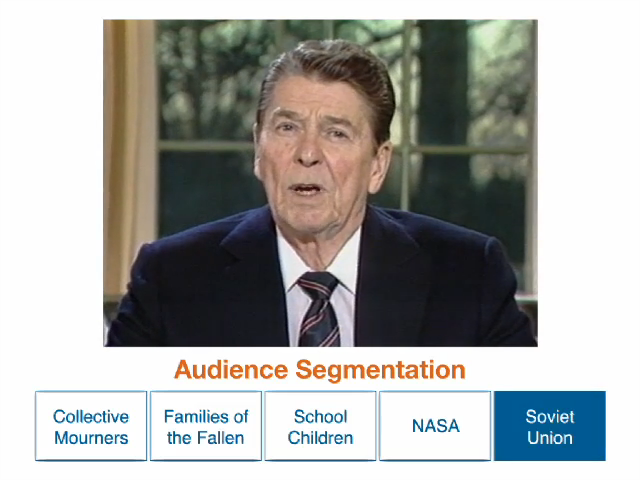

Case Study: Ronald Reagan

Space Shuttle Challenger Address

President Ronald Reagan was a skilled communicator who was faced with a daunting communication situation immediately after the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

The shuttle’s launch had already been delayed twice, and the White House was insisting that it launch before the State of the Union address, so it took off on January 28, 1986. This particular launch was widely publicized because for the first time a civilian—a teacher named Christa McAuliffe—was traveling into space. The plan was to have McAuliffe communicate to students from space. According to the New York Times, nearly half of America’s school children aged nine to thirteen watched the event live in their classrooms.2 After a short seventy-three seconds into flight, the world was stunned when the shuttle burst into flames, killing all seven crew members on board.

President Ronald Reagan cancelled his scheduled State of the Union address that evening and instead addressed the nation’s grief. In Great Speeches for Better Speaking, author Michael E. Eidenmuller describes the situation: “In addressing the American people on an event of national scope, Reagan would play the role of national eulogist. In that role, he would need to imbue the event with life-affirming meaning, praise the deceased, and manage a gamut of emotions accompanying this unforeseen and yet unaccounted-for disaster. As national eulogist, Reagan would have to offer redemptive hope to his audiences, and particularly to those most directly affected by the disaster. But Reagan would have to be more than just a eulogist. He would also have to be a U.S. President and carry it all with due presidential dignity befitting the office as well as the subject matter.”3

President Reagan’s ability to credibly move in and out of different roles for different audience segments was a large part of what made him The Great Communicator.

The speech succeeded in meeting the emotional requirements of its various audiences by carefully addressing each segment. The circumstances gave a natural situational segmentation; it would not have been appropriate for him to address them based on conventional distinctions of gender or political parties.

Reagan took care to connect all sub-audiences to the larger audience of collective mourners. He brought disparate groups together by treating them as a single organic whole: a nation of people called to a place of national sorrow and remembrance.

Eidenmuller says, “Catastrophic events do provide the basis for rhetorical situations. Despair, anxiety, fear, anger, and the loss of meaning and purpose are powerful psycho-spiritual forces that deeply affect us all. It has been said that ‘without hope the people perish.’ And without hearing powerful and timely words of encouragement, the people may never find cause for hope.”4

On the following pages, the various audiences Regan was addressing will be highlighted as he speaks. The speech lasted only four short minutes. The pages that follow show how carefully and beautifully President Reagan addressed the various audiences that evening.

Many insights from this analysis are from Michael E. Eidenmuller’s book Great Speeches for Better Speaking. The text in italics denotes direct quotes from his work.5

The State of the Union address is an annual, constitutionally sanctioned speech delivered like a national progress report—and is a significant task to reschedule. Reagan positions himself as both outside the fray and part of it. He presides over it and shares in its painful reality.

Reagan positions the tragedy within a larger picture without losing the significance of the present tragedy. He names each crew member and praises them for their courage. To further manage our emotions, Reagan again calls us to national mourning, and establishes the primary audience as the collective mourners.

Reagan narrows his focus to the first and most affected sub-audience: the families of the fallen. He acknowledges the inappropriateness of suggesting how they should feel and offers praise they can take hold of with words like “daring,” “brave,” “special grace,” and “special spirit.”

Reagan then draws attention back to the general audience’s interest in the larger scientific story. He then envisions the crew’s place in history as transcending science altogether by calling them pioneers. The term “pioneer” cloaks them in a mythical covering, one dating back to our nation’s earliest ventures. The astronauts’ death is portrayed as a reasonable outcome of their endeavors.

Reagan’s next sub-audience is the school children—an estimated five million—among whom are the students of Christa McAuliffe’s class and school. Reagan momentarily adopts the tone of an empathizing parent which is tough to do while remaining ‘presidential’, but Reagan carries it well.

Here, Reagan the national eulogist hands off to Reagan the U.S. President. This passage contains the only political statement in the address and is targeted at the Soviet Union. He attacks the secrecy surrounding their failures which had irked American scientists who knew that shared knowledge was the best way to ensure the stability and safety of space programs.

In this direct address to NASA, Reagan gives needed encouragement and then turns back again to connect to the whole audience by saying “we share it.”

In closing, Reagan creates an eloquent and poetic moment. It captures the mythological sentiment surrounding humanity’s unending quest to solve the mysteries of the unknown. The phrase “touch the face of God”, was taken from a poem entitled “High Flight” written by John Magee, an American aviator in WWII. Magee was inspired to write the poem while climbing to thirty-three thousand feet in his Spitfire. It remains in the Library of Congress today.

Meet the Hero

Audience segmentation is helpful—but there’s more complexity to human beings than that. To make a personal connection, you have to bond with what it is in people that makes them human. Take time to analyze who they really are and you will gain valuable insights. Remember, people you don’t know are difficult to influence.

At the beginning of a movie, the hero’s likeability is established. The same applies to a presentation. Successful Hollywood screenwriter Blake Snyder coined the phrase “save the cat” to describe a hero’s likeability. Snyder says that a “save the cat” scene is “where we meet the hero and he or she does something—like saving a cat—that defines who he is and makes the audience like him.”6 By answering the questions on the right, you’ll uncover what makes your hero likeable.

Liking your audience members is the first step in being genuine with them. Study them. What would a walk in their shoes feel like? What keeps them up at night? What are they called to do that will make a difference on this earth? Imagine their lives by the day, hour, and minute.

Don’t forget, they are only human, living chaotic lives. They might be worrying about a sick child, might have slept poorly in a hotel bed, might be struggling with financial problems, or just might feel they’re not in their groove. Think about how your idea will take away some of the pressure they’re feeling if they act on it. Consider where they are.

These questions help you think beyond what they do and focus on who they are. There’s a difference. It’s not enough to know their titles. If you’re speaking at a Human Resources event where your audience will mainly consist of Directors of Human Resources, look online and get an idea of what their typical salaries are. Do they make enough money to manage? How do these people most likely spend their paychecks? Does their role tend to attract people with certain temperaments? Are they impulsive or systematic?

Keep answering the questions until you move away from what your audience members do for a job and begin to acquaint yourself with who they are as people. You can imagine their childhood. What games did they play? What was home life like? What TV shows shaped their psyche? Anything that will generate a connection.

Your goal is to figure out what your audience cares about and link it to your idea.

Who They Are

LIFESTYLE

What’s likable and special about them? What does a walk in their shoes look like? Where do they hang out (in life and on the Web)? What’s their lifestyle like?

KNOWLEDGE

What do they already know about your topic? What sources do they get their knowledge from? What biases do they have (good or bad)?

MOTIVATION AND DESIRE

What do they need or desire? What is lacking in their lives? What gets them out of bed and turns their crank?

VALUES

What’s key to them? How do they spend their time and money? What are their priorities? What unites them or incites them?

INFLUENCE

Who or what influences their behavior? What experiences have influenced their thoughts? How do they make decisions?

RESPECT

How do they give and receive respect? What can you do to make them feel respected?

Meet the Mentor

Now that you’ve spent time getting into the audiences’ hearts and heads, it’s time to look at your role as mentor.

Mentors are selfless and think of themselves in the context of others. These exercises will help you think about yourself in terms of what you can give the audience.

Your role as mentor is to influence the hero (audience) at critical junctures of their life. The mentor’s appearance in the journey is essential to moving the hero past the blockades of doubt and fear. Mentors usually have two major responsibilities: teaching and gift-giving.

In the movie The Karate Kid (1984), Mr. Miyagi not only teaches protégé Daniel the “tool” of karate; he gives him insights into the meaning of life:

Miyagi: What matter?

Daniel: I’m just scared. The tournament and everything.

Miyagi: You remember lesson about balance?

Daniel: Yeah.

Miyagi: Lesson not just karate only. Lesson for whole life. Whole life have a balance. Everything be better. Understand?

Miyagi was a pretty smart dude. He got his deck sanded, car washed, plus his fence and house painted out of the deal. At times, there’s benefit to the mentor, but the greater benefit should always be for the hero.

What deep insights can you provide to your audience? Tap into your own life experience and use it to give to them a sense of how it would feel to follow their calling more fully. Don’t lose sight of the role you are playing in their lives.

The purpose of your appearance in their grand drama is to provide the tools and magical gifts that will help them get unstuck and continue on their journey. Of course you have an agenda and information to get across—maybe you’re even trying to close a deal—but you should offer something more in your presentation.

The mentor should provide the hero with important, useful, previously unknown information. You should also motivate the hero when he is fearful or hesitant, and give the hero tools for his tool belt. These tools could be roadmaps for success, new communication techniques, or even insights into his soul. No matter what the tool is, the audience should leave each presentation knowing something they didn’t know before and with the ability to apply that knowledge to help them succeed.

You mustn’t come across as if the audience is helping you on your journey. You’re to be a gift to them. Every once in a while, mentors gain something from the relationship for themselves, like knowledge or insights—but that shouldn’t be your goal. An audience can always spot selfish motives.

What You Give Them

GUIDANCE

What insights and knowledge will help them navigate their journey?

CONFIDENCE

How can you bolster

their confidence so

they aren’t reluctant?

TOOLS

What tools, skills,

or magical gifts do

they gain from you on their journey?

Create Common Ground

Creating common ground with an audience is like clearing a pathway from their heart to yours.

By identifying and articulating shared experiences and goals, you build a path of trust so strong that they feel safe crossing to your side.

You develop credibility without coming across as arrogant. Even your magnificent qualifications should be revealed in a humble and selfless way that connects with them.

Focusing on commonalities bolsters credibility, so spend time uncovering similarities. Seek out shared experiences and goals that you can bring to the foreground. A presentation that creates common ground has the potential to unite a diverse group of people toward a common purpose—people who normally might never have unified because of their great diversity.

People set aside differences when they’re strongly connected to achieving a common goal.

If a presentation goes badly awry, it’s easy to blame the audience for misinterpretations and say, “That’s not what I meant. How could they be so dumb?” In the blame game, all ten fingers should be pointed at you, not the people “misinterpreting” your presentation. You chose the words and images to convey your idea; if it didn’t align with the audience’s experiences, you need to own up to the misunderstanding.

I had one of those “why doesn’t the audience get this obvious idea” moments when conveying our company vision in 2007. My employees are not blind; my communication was flawed. Having been through three significant economic downturns, it was easy to see the next one coming a mile away. I knew that the firm needed to make some immediate changes that would help us weather the storm. But to the team, everything seemed safe and stable. So when I delivered an urgent “danger is eminent” message, it backfired. At the end of my dramatic presentation, my employees sat stunned, feeling like I was trying to manipulate them by telling them the sky was falling. What I thought was a presentation dripping with insight and urgency, my young staff—who had only known prosperity and stability—perceived as manipulative.

My message and means of communication slowed progress to a crawl. A handful understood, but getting everyone on board proved almost insurmountable. It took an entire year to reframe the issues and build momentum. Even though a downturn was coming, the idea had no traction because I didn’t use symbols or experiences to which my audience could connect.

The audience chooses whether to connect to you or not. People will usually respond only if it’s in their best interest. Personal values will ultimately drive their behavior, so ideally you should identify and align with existing values.

How You Connect with Them

SHARED EXPERIENCES

What from your past do

you have in common: memories, historical

events, interests?

COMMON GOALS

Where are you headed

in the future? What

types of outcomes are

mutually desired?

QUALIFICATIONS

Why are you uniquely qualified to be their guide? What similar journey have you gone on with a positive outcome?

Communicate from the Overlap

Why do you have to go through all these questions about the audience and yourself? Connecting empathetically with an audience requires developing understanding and sensitivity to their feelings and thoughts.

It’s the presenter’s job to know and tune into the audience’s frequency. Your message should resonate with what’s already inside them. As a presenter, if you send a message that is tuned to the “frequency” of their needs and desires—they will change. They might even quiver with enthusiasm and move together to create beautiful results (page 7).

When you are close with someone, your shared experiences create shared meaning. My husband, Mark, will often speak just one word that is packed with ample meaning, and I’m beside myself with laughter. It is safe to say that you haven’t known your audience for thirty years—but if you research them enough, they will feel like a close friend. And friends can easily persuade each other using an inherent way of swaying one another toward their point of view.

Establishing how you’re alike also clarifies how you’re different. Once you’ve identified the overlap, you’ll have a clearer understanding of what’s outside the overlap that needs to be embraced by the audience.

Your objective is to find the most relevant and believable way to link your issue to your audience’s top values and concerns.

Chapter 3 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.

In Summary

When you know someone, really know them, it’s easy to persuade them. Investing time into familiarizing yourself with the audience solidifies your ability to persuade.

Meet the Hero: The audience is the hero who will determine the outcome of your idea, so it’s important to know them fully. Jump into the shoes of your audience and look carefully at their lives. Picture them as individuals with complex lives. Identify with their feelings, thoughts, and attitudes. Discover their lifestyles, knowledge, desires, and values. Painting a picture of who they are in their ordinary world helps you connect with them and communicate from a place of empathy.

Meet the Mentor: Embracing the stance of mentor clothes you in humility. It moves you from forcing information on “an ignorant audience” to giving them valuable tools to guide them on their journey or help them get unstuck. They should leave with valuable insights they didn’t have before they met with you.

When an audience gathers, they have given you their time, which is a precious slice of their lives. It’s your job to have them feel that the time they spent with you brought value to their lives.

Rule #3

If a presenter knows the audience’s resonant frequency and tunes to that, the audience will move.