4Define the Journey

Preparing for the Audience's Journey

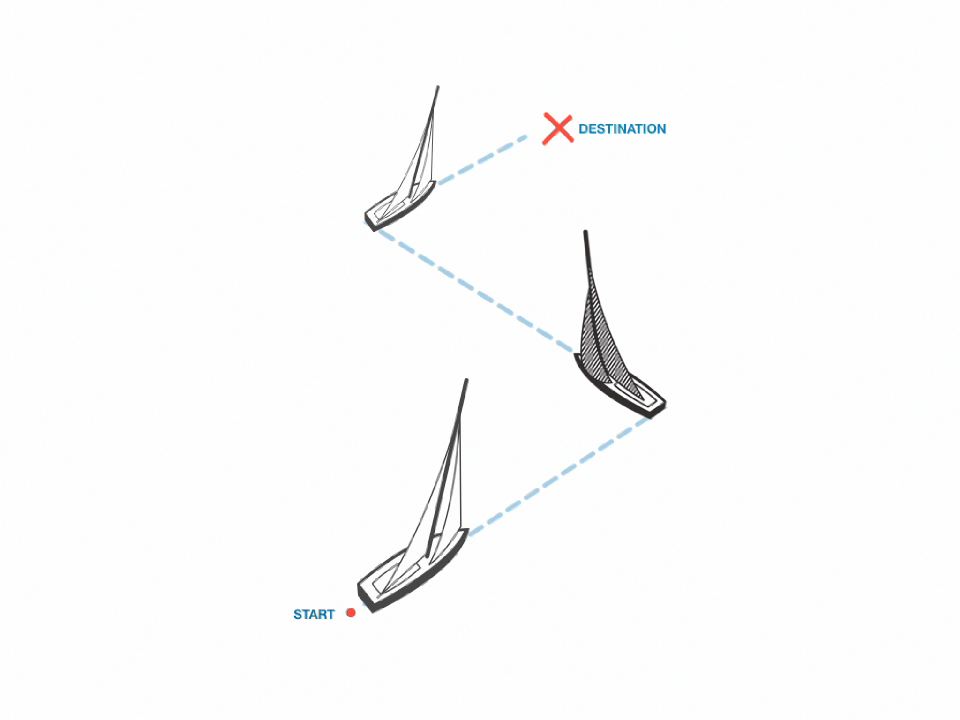

Good presentations lead an audience to a specific destination, and your audience won’t get there unless you map out where you want them to be when you’re finished presenting. A sailor who wanted to get to Hawaii would never simply jump into a boat, unfurl the sails, go wherever the wind took him, and expect to arrive there after a few days on the ocean. Traveling just doesn’t work that way—and neither do presentations. You have to set a course. Once you’ve set a destination, it will serve as a guide for developing the right content. Every bit of content you share should propel the audience toward that destination.

Remember, moving the audience from one place to another is the goal of every presentation. The audience will feel a sense of loss as they move away from their familiar world and closer to your perspective. You are persuading the audience to let go of old beliefs or habits, and adopt new ones. When people deeply understand things from a new perspective to the point where they feel inclined to change, that change begins on the inside (heart and mind) and ends on the outside (actions and behavior). However, this typically doesn’t happen without a struggle.

That struggle usually manifests as resistance—but you can harness that resistance and use it to your advantage if you plan well. When a sailboat’s sails are set correctly, it can sail into the wind and still harness the wind’s power. In fact, a boat can sail faster than the wind itself—even when the gusts are in the opposite direction. Of course you can’t control the strength of an audience’s resistance, but you can “adjust your sails” (message) and use that resistance to gain momentum. When properly harnessed, forces that seem counterproductive can lead to forward progress. However, the boat (your presentation) needs to move back and forth in order to get there, just like the Presentation Form.

The journey should be mapped out and all related messages should propel the audience closer to the destination.

Plan the Audience's Journey

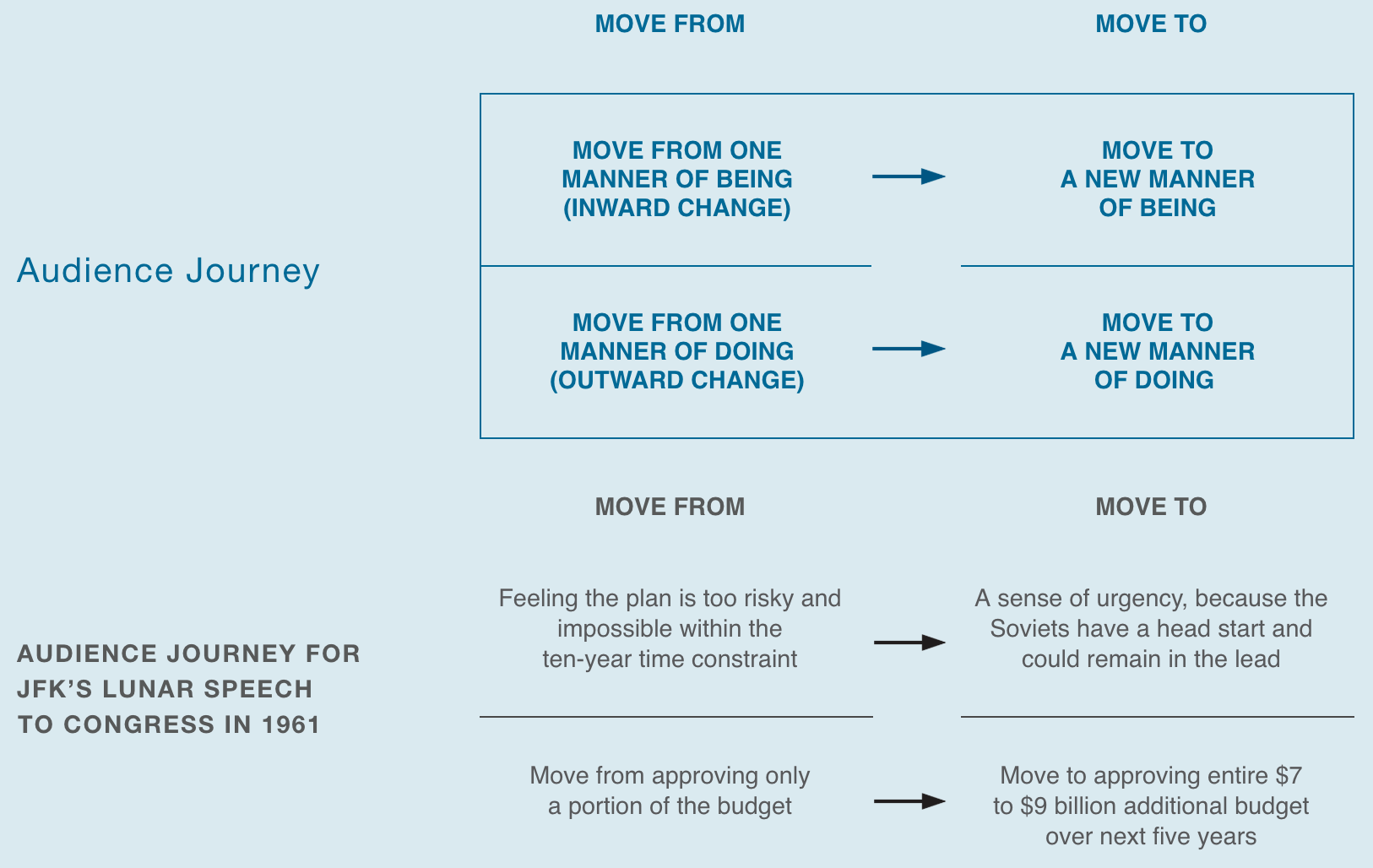

Now you have established your big idea and determined your destination. But you also need a map—a persuasion plan. Persuasion involves asking your audience to change in one way or another, and change usually obligates people to move from their current way of being or acting and move to a new and different way of being or acting. Often, internal emotional changes must transpire before people manifest external change in their behavior.

Change is interesting to watch. We go to the movies or read a book to see the change that happens in the main character. This carefully planned change is called the character arc—the identifiable internal and external change that the hero endures.

When a screenplay is submitted for acquisition to a studio, a story analyst evaluates it by assessing the quality of the character arc. The story analyst determines the quality fairly quickly, simply by looking at the first and last pages of the script.

The first page sets up who the hero is when the movie begins and the last page determines how much the hero changed during its course. This quick assessment of a screenplay determines if the hero’s journey changed her at all. If the hero didn’t change enough, it’ll be a boring film.3 Great stories show growth and transformation in the characters.

In the same way a story analyst looks at the first and last page of a screenplay, you must envision and study your audience at the beginning of your presentation—and who you want them to be when they leave. Upon entering the room, your audience holds a point of view about your topic that you want to change.

You want to move them from inaction to action; you want them to leave the room holding your perspective as dear and committing to it. This won’t happen without a carefully planned map.

When planning your audience’s journey, you have to establish where they are and where you want to move them to. Identify both the inner and outer transformation you want to achieve. If you can persuade them to change internally, you will usually see results in their actions. This outward change proves that they understood and embraced your big idea. When beliefs change, actions follow.

You might be thinking, “Gosh, I’m just presenting at my staff meeting, I can skip this step.” Perhaps a better option, in that case, would be writing and distributing a report. Although, if your staff meeting is about the status of a project that is over budget, you better get in there and move them from thinking that being over budget is okay, to taking responsibility and working hard to ensure the budget gets back on track. This, then, is a persuasive situation that requires a clearly defined journey.

The Big Idea

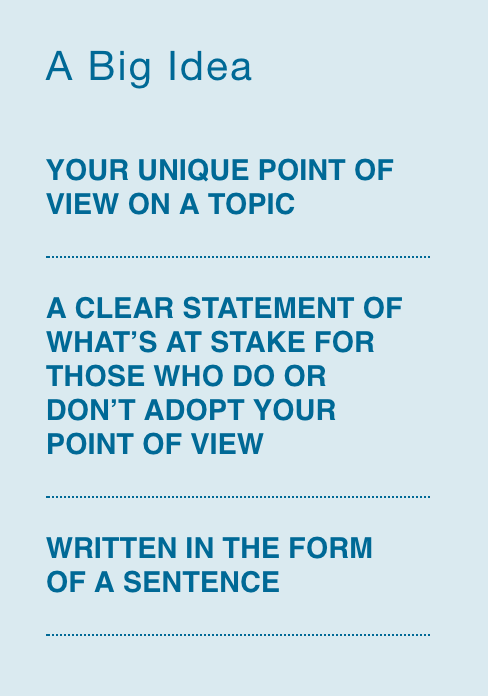

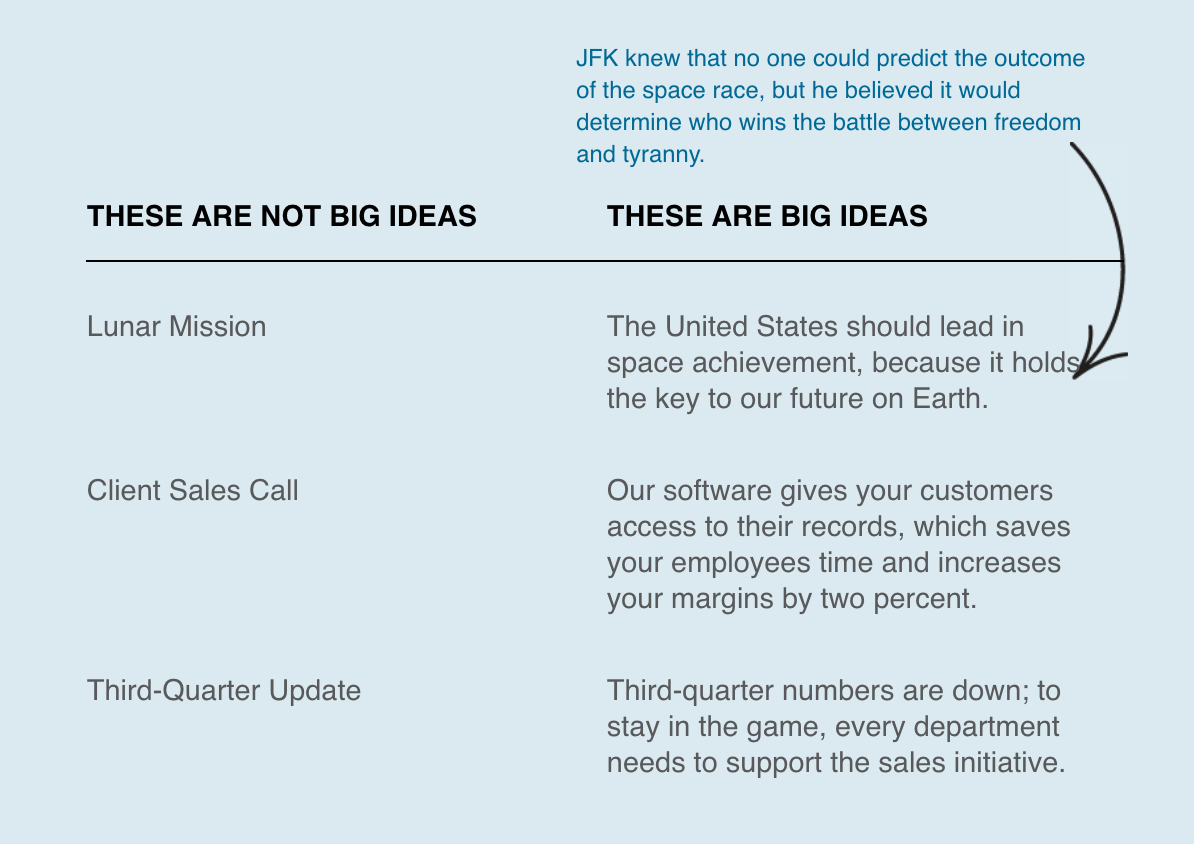

A big idea is that one key message you want to communicate. It contains the impetus that compels the audience to set a new course with a new compass heading. Screenwriters call this the “controlling idea.” It’s also been called the gist, the takeaway, the thesis statement, or the single unifying message.

There are three components of a big idea:

ONE A big idea must convey your unique perspective. Your audience showed up to hear you speak. They’re sitting there to learn your point of view, and you should clearly and completely articulate it. For example, “the fate of the oceans,” is only a topic, not a big idea. “Worldwide pollution is killing the ocean and us,” is a big idea with a unique perspective. Your big idea doesn’t need to be so unusual that no presenter has ever expressed it before. But it must be unique to you, not merely a generalization.

TWO A big idea must communicate what’s at stake. You need to articulate to the audience why they should care enough about your perspective to adopt it. The big idea, “Replenish the wetlands through new legislation,” doesn’t convey what’s at stake. In contrast, “Without better legislation, the destruction of the wetlands will cost the Florida economy $70 billion by 2025,” provides a strong reason to care. When you convey what’s at stake, you help your audience understand why they should participate and become heroes. Without compelling reasons for the audience to engage, your big idea won’t get off the ground.

THREE A big idea must be stated as a complete sentence. When you state your big idea as a complete sentence it forces you to use a noun and a verb. If presenters are asked what their presentation is about, they usually respond with phrases such as, “the third quarter update,” or “our company’s new software.” These are not big ideas. A big idea must be expressed in a complete sentence such as, “This software will increase your team’s productivity 10 percent and boost

revenues over the next year by $1 million.” Using “you” in the sentence makes it even better, because it ensures that you have a clear audience in mind.

Emotion is another important component to the big idea. Boiling down all of the various emotions simplifies this task. Ultimately, there are only two emotions—pleasure and pain. A truly persuasive presentation plays on those emotions to do one of the following:

- Raise the likelihood of pain and lower the likelihood of pleasure if they reject the big idea.

- Raise the likelihood of pleasure and lower the likelihood of pain if they accept the big idea.¹

For example, a business presentation that centers on “We are losing our competitive advantage” as its big idea, has nothing at stake. In contrast, the message “If we don’t regain our competitive advantage, your jobs are in jeopardy” makes it clear that there’s plenty at stake!

It appeals to employees’ human instinct to survive. Humans change when there is a threat and sense of urgency. In the January 2007 issue of Harvard Business Review, John P. Kotter explained “most successful change efforts begin when some individuals or groups start to look hard at a company’s competitive situation, market position, technological trends, and financial performance. They then find ways to communicate this information broadly and dramatically, especially with respect to crises, potential crises, or great opportunities that are very timely.”2

The gravity of the presentation should match the severity of the situation and accurately reflect what’s at stake—no more, no less.

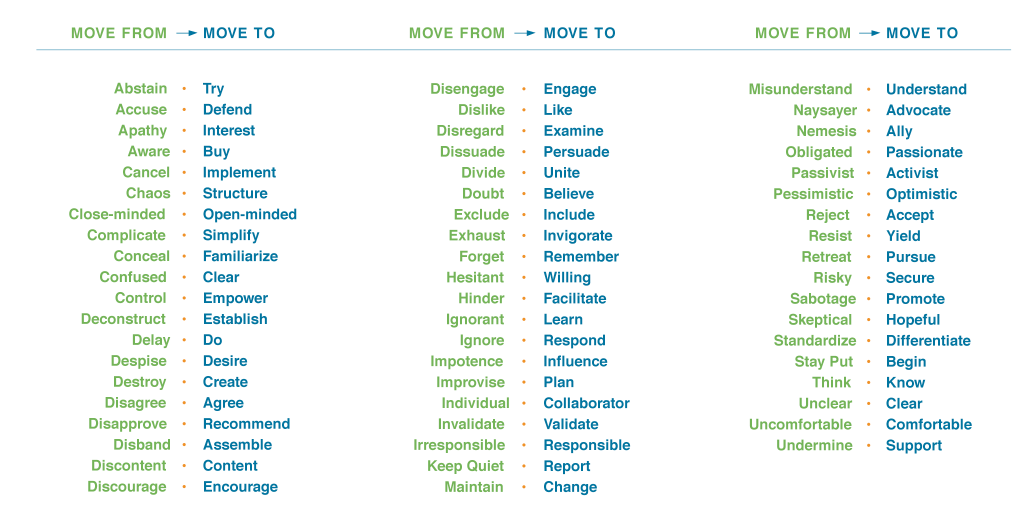

Tools for Mapping a Journey

Below is a list of words pulled from various articles on change management. It’s not an exhaustive list of every type of change, but it can help spark ideas for how you want your audience to be transformed.

Acknowledge the Risk

People experience a sense of fear when they embark on a journey that involves change, because change has an element of the unknown. That is what makes it so frightening.

Change is about accepting the new and abandoning the old. New societies cannot rise unless old societies fall. If new technology emerges, it renders the old technology obsolete. In the presentation space, accepting something new often means sacrificing something held dear.

Sacrifice is defined as the surrender or destruction of something prized or desirable for the sake of something considered as having a higher or more pressing claim. Often, your audience can’t change without making a sacrifice. You need to make them understand that without sacrifice, there can be no reward.

To adopt your perspective, the audience has to, at a minimum, abandon what they previously held as true.

Changing their minds is like asking them to forsake an old friend who has stood by them for a long time. Losing an old friend is painful.

Even something seemingly trivial—like a forfeit of their time—might require them to risk something. Working late might mean missing volleyball practice or the chance to tuck their kids into bed at night. Be cognizant of the sacrifice the audience will make when you ask them to do something, because you’re asking them to give up a small—but still irretrievable—slice of their lives.

Audience resistance is usually related to the sacrifice they realize they will have to make. Presentations disrupt the audience’s contented stance. Perhaps they’ll have to give up time or money. You’re telling them they will be better off if they buy your product, or become more productive, or join a movement, but they think everything is okay the way it is.

Change requires a breaking down before there’s a building up, and this is where the audience needs the encouragement from the mentor most of all.

Audience transformation is guided along a grand plan similar to the metamorphosis of a butterfly. After the caterpillar creates a hard, protective cocoon, what happens on the inside is almost tumultuous. The solids of the caterpillar liquefy and regroup into a completely different form. A butterfly.

Empathize with Their Sacrifice and Risk

SACRIFICE

What would they sacrifice

to adopt your idea? What beliefs or ideals will be let

go? How much will it cost

them in time or money?

RISK

What’s the perceived risk?

Are there physical or emotional risks they will need to take? How will this stretch them? Who or what might they have

to confront?

Address Resistance

Refusal of the Call

There’s no doubt about it; most people do not enjoy change and will resist. An audience might understand your plea, and even mentally accept it, but they still might not be moved to action.

In the July 2008 issue of Harvard Business Review, John P. Kotter and Leonard A. Schlesinger reported, “All people who are affected by change experience some emotional turmoil. Even changes that appear to be ‘positive’ or ‘rational’ involve loss and uncertainty. Nevertheless, for a number of different reasons, individuals, or groups can react very differently to change—from passively resisting it, to aggressively trying to undermine it, to sincerely embracing it.”4

Some audience members will oppose your ideas or look for holes in your argument because if they don’t, they’re either forced to live with the contradiction between their old perspective and the new one you’ve “sold” them, or opt to change.

Their resistance can range from subtle skepticism to open revolt, and you must be prepared to deal with it. When you’re sailing into the wind, you can still move towards your destination, but you must adjust your “sails,” modifying your arguments to move audience members from aggressively attacking your message to whole-heartedly embracing it.

Carefully contemplate all the ways in which your audience might resist. What attitudes, fears, and limitations do they use as a tool to oppose implementing the idea? After identifying their reasons for refusal, use those concerns as inoculants. State the opposing points before they get a chance to refute your point.

An inoculation purposefully infects a person to minimize the severity of an infection. The same takes place when you empathetically address an audience’s refusals by stating them openly in your talk. This will help them see that you’ve thought through everything—which will decrease their anxiety.

It is not common for people to resist merely for the sake of resistance (although some do). In general, people resist because you’re asking them to take a risk or make a sacrifice, at least to some degree. For example, if you ask them to buy your company’s product it could make them worry that they’re putting their reputation at risk by committing company money to a product with an uncertain outcome.

Your audience may view what you experience as resistance in an entirely different light. From their perspective, it may seem that your message puts their credibility, reputation, or even their honor at risk. It may be that where you see resistance, they see valor. They feel they are responding appropriately to protect things they value and hold dear. Acknowledge their resistance while at the same time assuring them that with you, their mentor, they are in good hands.

Refusal of the Call

COMFORT ZONE

What’s their tolerance level

for change? Where is their comfort zone? How far out

of it are you asking them

to go?

FEAR

What keeps them up at night? What’s their greatest fear?

What fears are valid, and

which should be dispelled?

VULNERABILITIES

In which areas are they vulnerable? Any recent changes, errors, or weaknesses?

MISUNDERSTANDING

What might they

misunderstand about the message and/or implications? Why might they believe the change doesn’t make sense

for them?

OBSTACLES

What mental or practical barriers are in their way?

What obstacles cause

friction? What will stop them from adopting and acting on your message?

POLITICS

Where is the balance of

power? Who or what has influence over them?

Would your idea create a

shift in power?

Make the Reward Worth It

Whether it’s based on altruism or ego, people like to make a difference with their lives. That difference could be something as modest as “make this a great place to work” or as lofty as “save lives in Ethiopia.”

No matter how engaging your presentation may be, no audience will act unless you describe a reward that makes it worthwhile. You must clearly articulate the ultimate gain for the audience, its extended sphere of influence, or perhaps even all of humanity. If your call to action is asking them to sacrifice their time, money, or ideals, you must be very clear about what the payoff will be.

Rewards should appeal to physical, relational, or self-fulfillment needs:

- Basic needs: The human body has basic needs like food, water, shelter, and rest. When any of those are threatened, people will risk life and limb to secure

them—even for someone else. People don’t like to see others’ basic needs go unmet, and this prompts generosity.

- Security: People want to feel secure and safe at home, at work, and at play. Physical, financial, or even technological security assures them that they are safe.

- Savings: Time and money are two precious commodities. Your presentation’s reward might be to save the audience time or create a generous return on their investment.

- Prize: This can be anything from a personal financial reward to gaining market share. It is the privilege of taking possession of something.

- Recognition: People relish being honored for their individual or collective efforts. Being seen in a new light, receiving a promotion, or gaining admission into something exclusive are all credits that can work.

- Relationship: People will endure a lot for the promise of community with a group of folks who make a difference. A reward can be as simple as a victory celebration with those they love.

- Destiny: Guiding the audience toward a life-long dream fulfills the need for being valued. Offer the audience a chance to live up to their full potential.

In light of these categories, ask yourself: what is it that the audience gets in exchange for changing? What is in it for them? What do they gain by adopting your perspective or buying your product? What value does it bring to them?

As you’ve learned from The Hero’s Journey, the hero leaves the ordinary world, enters a special world, and returns not only changed as a human being, but bearing an Elixir—a reward for having taken the journey. The reward for your audience should be proportional to the sacrifice they have made.

Identify the Reward (New Bliss)

BENEFIT TO THEM

How will they personally benefit from adopting your idea? What’s in it for them materially or emotionally?

BENEFIT TO SPHERE

How will this help their sphere of influence such as friends, peers, students, and direct reports? How can they use it to their benefit with those they influence?

BENEFIT TO MANKIND

How will this help the humans or the planet?

Case Study: General Electric

Showing the Benefit of Change

As one of the largest corporations in the world, General Electric views innovation as a prize commodity. It is in a constant state of flux due to the tension that arises between what is and what could be, as employees seek to solve the problems of today while imagining the innovations that will shape tomorrow. One aspect of this process is that old innovations are often destroyed to make room for new ones.

Communicating within this atmosphere of innovative tension isn’t always easy. Chief Marketing Officer, Beth Comstock, has led a team that has navigated this territory effectively. Many of Comstock’s presentations address the contrast of what is versus what could be.

Comstock delivered the presentation featured on the next few pages to persuade her sales and marketing team that “growth in a downturn” is possible (notice the contrast even in her title). She wanted to move her team from the defeatist mindset of a downturn (what is) to believing they could innovate in a downturn (what could be). It’s common for her presentations to address the theme of navigating through the tension of innovation.

Comstock sprinkles her communication with personal stories of risk, frailty, and victories, which makes her credible and transparent. She once even shared how previous GE CEO, Jack Welch, called her only to hang up the phone mid-sentence. When Comstock called his assistant, she was told, “He’s teaching you a lesson—that’s how you come across sometimes.” It was a stark lesson about leading and coaching with humor.

Comstock is a natural at communicating contrast. The set-up of her script (below) is still in its original prose form, but the content has been edited on the following pages into a “move from,” “move to,” “benefit,” and “personalized story” matrix so you can see the brilliant, underlying structure she inherently used.

Growth in a Downturn?

Jeff Immelt took over as CEO of GE in 2001 with a strategy to grow the company from within, while investing more in technology/innovation, global expansion, and customer relationships. To make this happen, GE needed a stronger marketing organization to sit beside technology, sales, and the regional business leaders. For decades, GE was so confident in its products that it believed the products could practically market themselves. Then, a collective awakening occurred: seasoned marketers could push GE to go more places, organize technologies to accomplish new feats, and help point the company in the direction of even more sales.

GE set an aggressive course in 2003 to double its marketing talent and build new capabilities. Comstock was the first CMO in decades. GE marketers established a marketing-led innovation portfolio and process across GE that creates between $2 and $3 billion dollars a year in new revenue. Through this effort, GE defined marketing innovation as a necessary partner for technical and product innovation. Marketers were a critical part of the team that drove eight to ten percent organic growth, more than double the historic rate.

But by 2008, a global economic crisis was wreaking havoc on growth rates and changing customer behavior. What happens when growth stalls? Was it time for GE to cut marketing? The decision was just the opposite. Marketing needed to be valued as a function for all seasons.

Comstock was inspired by research conducted by Harvard Business School’s Ranjay Gulati. Gulati observed that companies that relentlessly focus on the customer and invest more in the pipeline in a downturn can expect to stay ahead for up to five years after recovery. Now, that gets your attention!

GE’s goal in 2008 was to stay focused on growth, no matter how tough the environment. GE needed to plant seeds so it would be poised when recovery happened. That meant investing in new opportunities and encouraging new ideas.

Foster Creativity

Move to Being

Move from being uncomfortable with creativity to believing that everyone can be creative—it’s frightening to move outside a comfort zone.

Benefit/Outcome

Creativity takes planning in multiple iterations, but good process helps ideas stick and energizes the team.

Move to Doing

Move from chaotic to organized through “freedom within a framework.” Define the problem, make room for ideas, and work as individuals and teams.

Personalize

A team of nuclear scientists went behind the scenes at NASCAR to learn similarities in the way race cars and nuclear plants are serviced. For me, keeping an idea journal is a helpful way to create a “space” to ideate.

Navigate Ambiguity

Move to Being

Move from being paralyzed by not knowing all the answers to accepting that you will never know all the answers..

Benefit/Outcome

Removing ambiguity helps you face reality, make the tough calls, and be flexible with new approaches.

Move to Doing

Move from fear of starting to picking a path, knowing that where you end up could be very different than where you started.

Personalize

Jack Welch taught me the importance of wallowing. Having spent many years in fast-paced news environments, Jack taught me how to get to know ideas and people.

Take Risks

Move to Being

Move from being afraid of instigating ideas to fighting for a better way. Instigators are rarely welcomed, but are critical to the creative process.

Benefit/Outcome

If you do not jump in, you will regret the missed opportunity. When you fail fast, you fail small.

Move to Doing

Move from low visibility to moving forward without the answers. Ideas need a champion to turn them into action, so executive buy-in is critical.

Personalize

I needed to overcome my reserve. Sometimes I look back to when I knew I could add value, then regret the missed opportunity. Now I tell myself, “You don’t want to miss this. Get in there.”

Develop New World Skills

Move to Being

Move from being a technophobe to seeing that in a networked world, value comes from who you are connected to.

Benefit/Outcome

Transform your sphere of influence and turn your network into an asset that predicts future actions, needs, and solutions.

Move to Doing

Move from the illusion of control to inviting others to join with you. Your best selling machine can be validation from customers in your network.

Personalize

The Obama campaign understood the power of a decentralized network of people who shared a passion for change in the political systems. They were given access to key tools, information, and the freedom to use them.

Empower Teams

Move to Being

Move from going it alone to forming partnerships, because teams with multiple points of view create diverse solutions.

Benefit/Outcome

Partnerships allow you to share risk, fill in capability gaps, and focus expertise.

Move to Doing

Move from fear of criticism to recognizing tension as an important part of the creative process. Give critics a voice, and they’ll become advocates.

Personalize

I believed I had to do it all myself and didn’t ask for help. I learned that you have to invite others in and that it’s okay to admit you need help. People want to help and be part of something bigger than themselves.

Unleash Your Passion

Move to Being

Move from lacking passion to encouraging passion—yours and theirs. Lack of passion stalls ideas, so start and end with passion.

Benefit/Outcome

You create an energy that builds on itself, that creates momentum and engagement from others.

Move to Doing

Move from personal passion to shared passion blended with compassion—it creates an energy that propels projects and meets needs.

Personalize

I’ve learned that sometimes my passion can overwhelm others, especially if it borders on aggressiveness. I’ve had to let ideas germinate and encourage others to add to them and make them their own.

Chapter 4 Review

Review what you’ve learned so far. Each question has one right answer.

In Summary

Most audience members are comfortable with the view from their own perspective and don’t like to admit there might be another valid perspective out there. When you propose your idea, it forces them to make a decision either to adopt your idea or live with the consequence of refusing to adopt your idea.

To ensure your idea is adopted, it’s important to have a plan—a definitive destination. Determining the destination involves creating a big idea (with the stakes articulated). You also need to plan out the audience journey of where you want them to move from and where you want them to move to.

They will possibly (okay, most definitely) initially react to your proposed change with resistance. Address the resistance and risks involved so their fears are pacified and they are willing to jump in.

Make sure the benefit is clear to them. You’re persuading them to change, and there has to be something in it for them, their organization, or mankind to make it worthwhile.

Rule #4

Every audience will persist in a state of rest unless compelled to change.